“If . . . Æsop has pictures in it, it will entertain [children] much the better, and encourage [them] to read, . . . ideas being not to be had from sounds, but from the things themselves or their pictures” –John Locke, Some Thoughts Concerning Education, 1693 (212)

The Visible World in Pictures

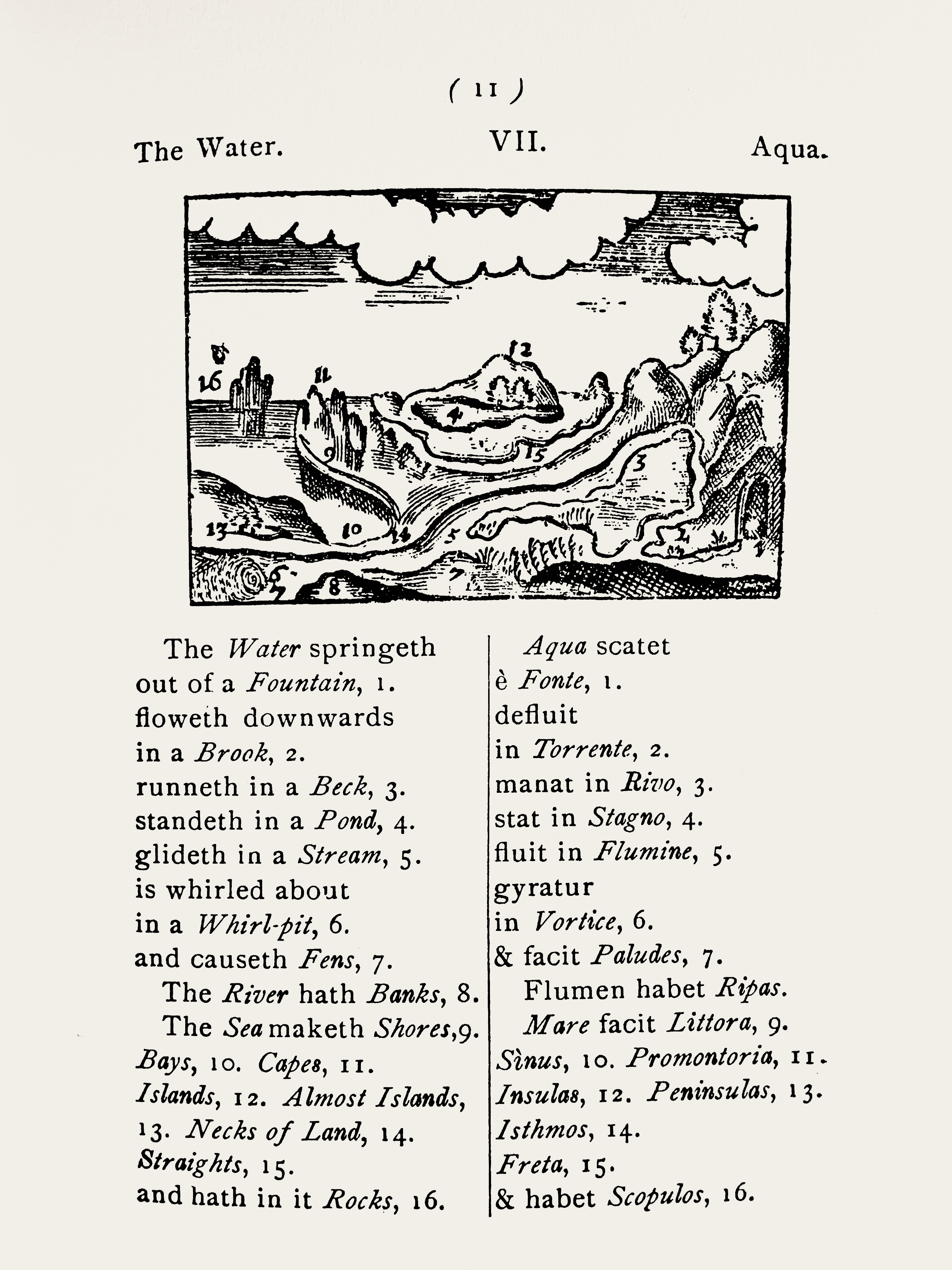

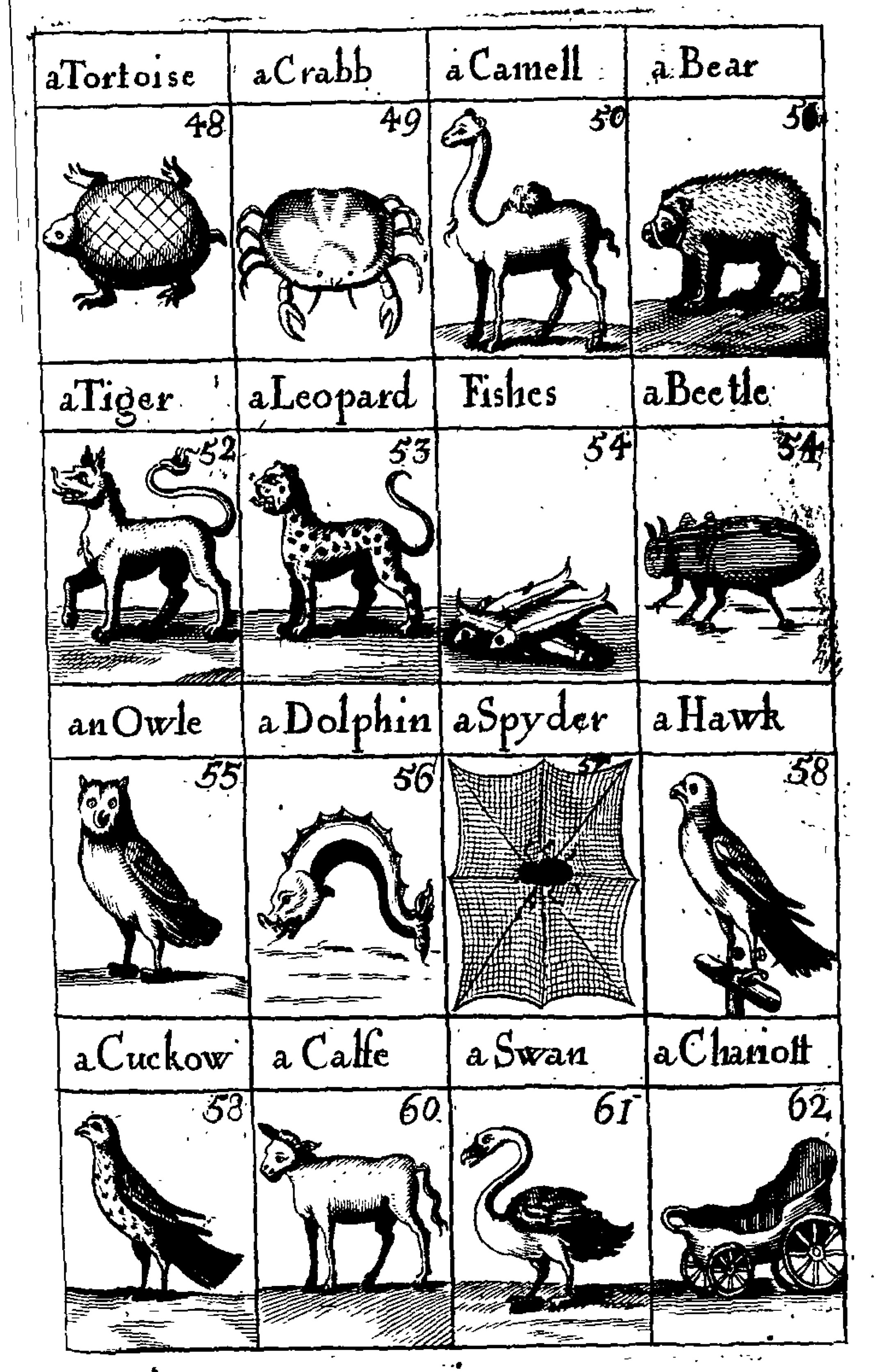

Looking for an origin story for illustrated children’s literature is almost like a treasure hunt—some scholars view the fifteenth-century versions of Aesop’s Fables as the earliest illustrated books for children, although they were not exclusively aimed at a young audience. However, the notion of the illustrated children’s book emerged more definitively in the seventeenth century, with the publication of The Visible World in Pictures (Orbis sensualium pictus, 1658), a Latin textbook that also served as an innovative, illustrated encyclopedia, and is often credited as the first picture book for children. Created by Comenius (also known as Jan Amos Komensky, 1592–1670), a Czech bishop in the Bohemian Brethren, this work pioneered the notion of teaching through images of concrete objects instead of abstract concepts, and exerted an enormous influence on subsequent children’s books in Europe (Carpenter & Prichard 1999, 388; Hürlimann 1967, 127–36; Nodelman 1988, 2).

Back to Top of Page

Aesop & Locke

Echoing Comenius’s approach just a few decades later, John Locke (1632–1704) declared that books should be illustrated to encourage children to read: “ideas being not to be had from sounds, but from the things themselves or their pictures” (1693, 212). To emphasize this notion, Locke edited an illustrated edition of Aesop’s Fables (1703), in which he foregrounded the visual appearance of the animals rather than the narratives. Locke’s legacy to children’s literature, as Seth Lerer points out, is his emphasis on the children’s book as a means to make sense of the concrete particulars of daily life; Locke calls these “playthings” but this includes not just toys, but also scraps of paper, pebbles, “ill-strewn closets,” and books themselves (Lerer 2008, 106–7, 111–13).

Back to Top of Page

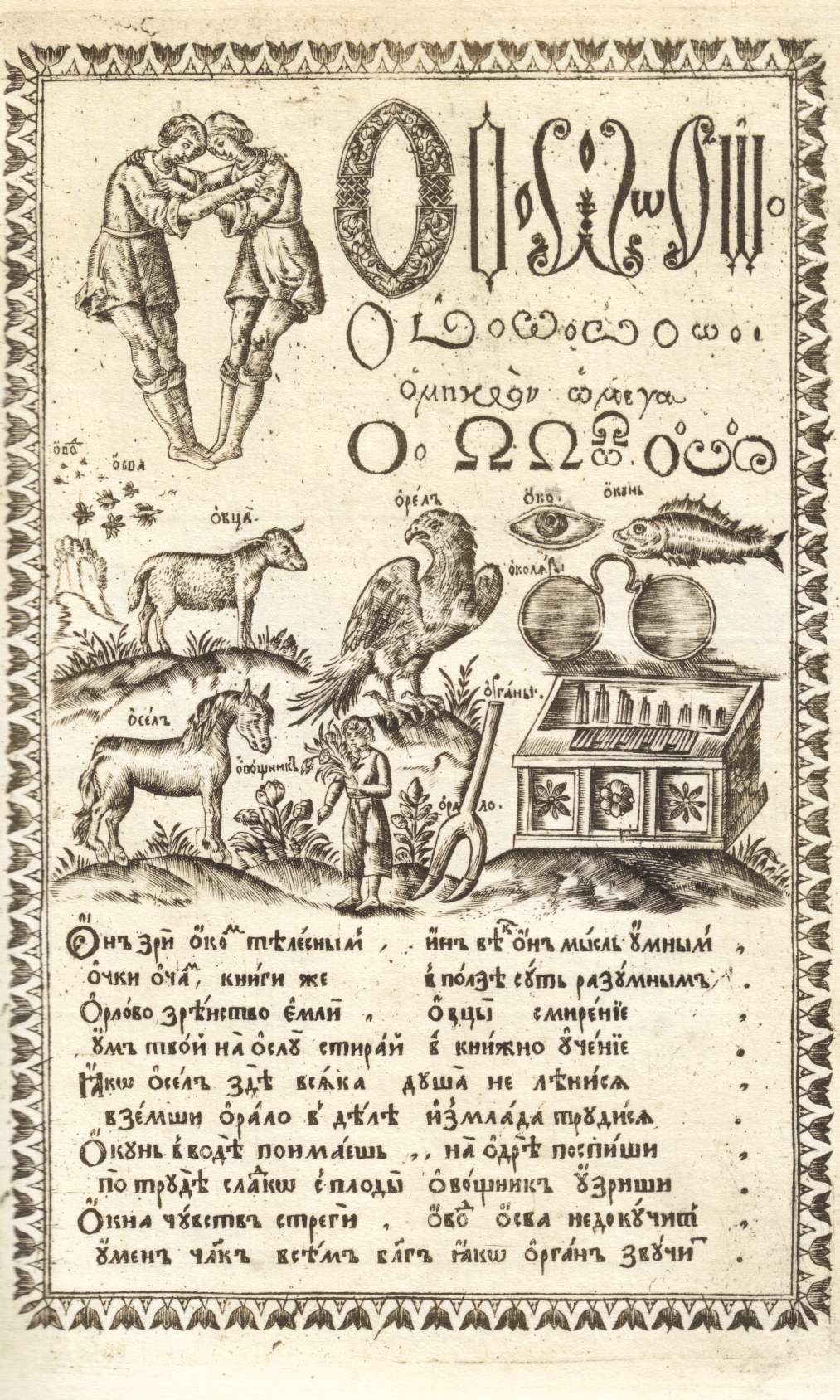

In Russia in the same decade, Karion Istomin (c. 1640s–c. 1717), a tutor at the Russian royal court, produced one of the earliest illustrated Russian children’s books: the Illustrated Primer (Лицевой букварь, c. 1694; also known as the Great Primer), which included an elaborately designed picture for each letter of the alphabet. Many scholars single out Istomin as the first significant Russian writer of children’s literature, because his works demonstrate playfulness and empathy for the child’s perspective. Looking ahead to the flowering of Russian illustrated books at the turn of the 20th century, we could name Istomin as a father of that trend, for he emphasized the importance of illustration in children’s books (Hellman 2013, 1–2; Voskoboinikov 2014, 14–15; Rosenfeld 2014, 168).

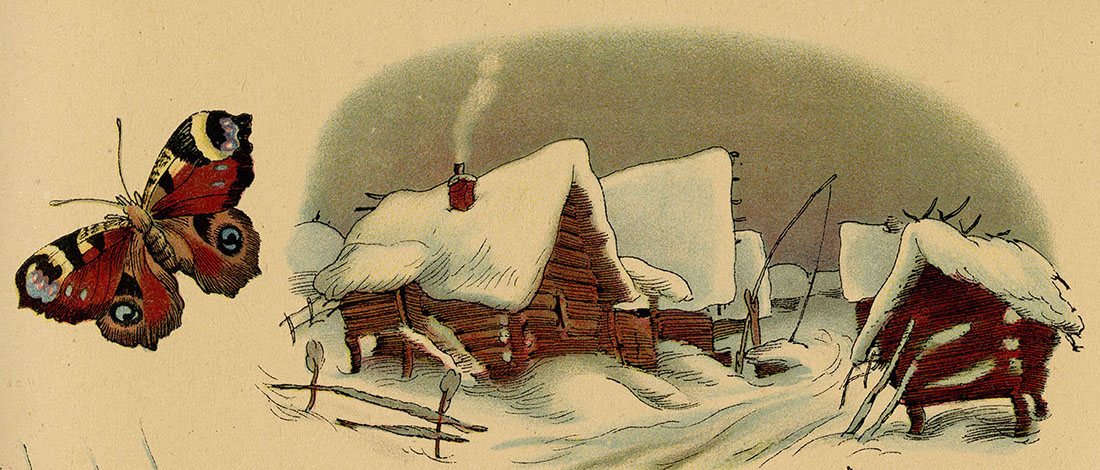

Further groundwork for the Russian illustrated children’s book was laid by the pioneering eighteenth-century figure Nikolai Novikov (1744–1818), who founded the first Russian children’s journal, Children’s Literature for the Heart and Mind (Децкое чтение для сердца и разума, 1785–89), and published several children’s books throughout the 1780s. Novikov was “the first in Russia to recognize children as a separate public” (Lemmens & Stommels 2009, 40), and in this Novikov embodied the spirit of his age, influenced by Rousseau’s ideas regarding the importance of childhood and education. His legacy to the children’s picture book lies in his particular emphasis on the role of illustration, including “exquisite vignettes, frontispieces, and tailpieces,” as well as illustrations of the “highest quality” (Rosenfeld 2014, 170).

Back to Top of Page

The Arrival of Lithography

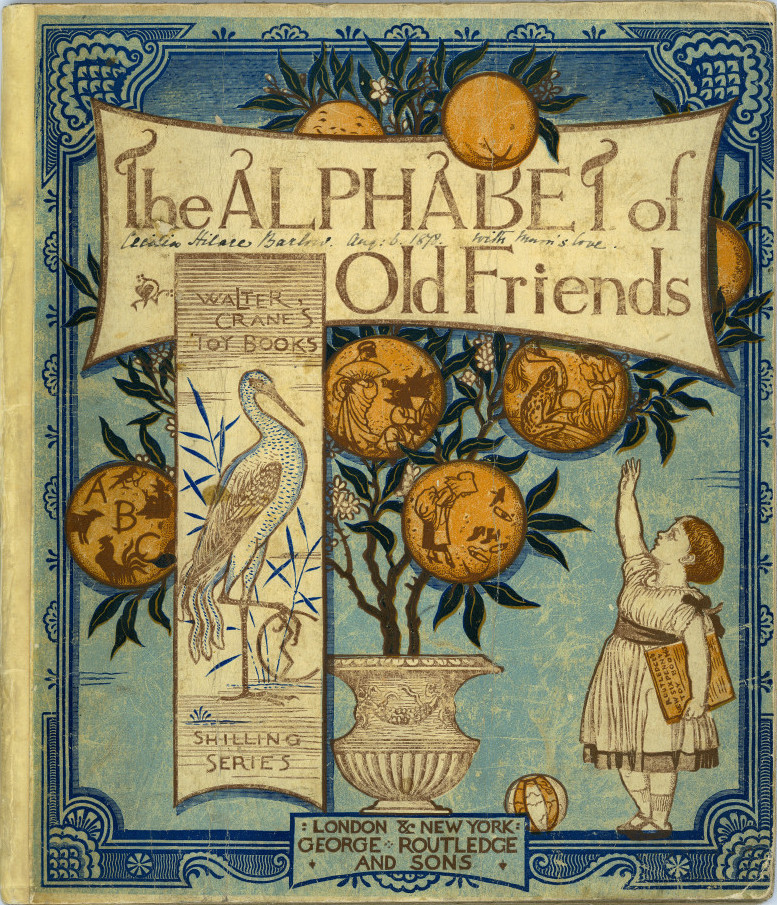

John Newbery (1713–67) is often credited for founding the first English publishing house to emphasize visually appealing literature for children and to advocate Lockean ideals of play, but many argue that “the first masterpiece of children’s book illustration” arrived a few generations later, embodied by George Cruikshank’s illustrations for the English translation of Grimm’s Fairytales (German Popular Stories, 1823), which laid “the cornerstone for the ‘Golden Age’ of children’s book illustration” (Hearn 1996, 7; T. Clark 1996, 57). In its wake, innovations in printing techniques, including chromolithography, revolutionized the illustrated children’s book by the mid-nineteenth century. The master in nineteenth-century printing techniques was the renowned English printer Edmund Evans (1826–1905), who helped perfect mechanical color printing and emphasized the importance of both illustration and overall book design. Around 1865 Evans began his renowned collaboration with Walter Crane (1845–1915), who became one of the most eminent children’s book designers of his time (T. Clark 1996, 57; Briggs & Butts 1995, 164; Carpenter & Prichard 1999, 170 & 537).

Crane pioneered the notion of the book itself as a work of art, and greatly influenced Russian book design. Like other artists in this era of Japonisme, Crane was inspired by Japanese woodblock prints, which he praised for their “strong outlines, and flat tints and solid blacks” (1896, 156–58). He argued that “book illustration should be something more than a collection of accidental sketches” and that “the idea of the book itself” should always be taken into account when designing any of its parts (217). In The Baby’s Bouquet (1878), for which he designed and decorated every element including the front matter and end papers, Crane achieved this vision of the book as a work of art in itself: “Here finally was the modern artistic picture book, and every illustrator in the field owes much to Crane’s legacy” (Hearn 1996, 11). Randolph Caldecott and Kate Greenaway, the two other renowned illustrators of this era who also worked with Evans, brought a different sensibility to their craft. Their books exude nostalgia for an elusive past, especially the eighteenth century (Lerer 2008, 325; Hearn 1996, 13). In this they are strikingly similar to the sensibility of the Mir Iskusstva (World of Art) movement in Russia, especially as embodied by the work of Alexandre Benois, as will be seen in the next essay.

Back to Top of Page

In Russia, as in the West, the advent of lithography transformed the illustrated children’s book. But the true revolution in Russian children’s book design came with the arrival of the Neo-Russian style, which was linked to the revival of Russian peasant crafts in the 1870s, paralleling Western revivals such as William Morris’s Arts and Crafts movement. In Russia, members of the elite and educated classes, mourning the disappearing craftsmanship of the kustar (“peasant handicraftsman”), created workshops in the countryside to encourage villagers to practice traditional crafts instead of moving to cities to work in factories (Salmond 1996, 1–8).

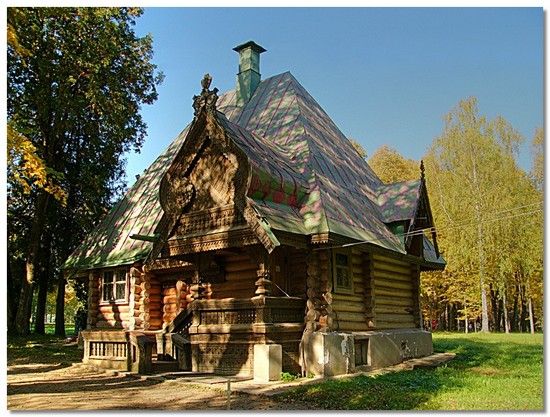

One of the most important centers of the kustar revival and the Neo-Russian style was in the Abramtsevo Circle, a neo-romantic group that formed in 1878 around the Abramtsevo estate of the railway entrepreneur Savva Mamontov (1841–1918), whose members collaborated in furniture design, theatrical set decoration, costume design, architecture, embroidery, and book illustration. Abramtsevo amateur theatrical productions laid the groundwork for the innovative Russian stage design of the early twentieth century, which became famous in the West thanks to Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes. Like Diaghilev, Mamontov was a larger-than-life figure with grand ambitions; he has been called the “Russian Medici” (Iovleva 2007, 34). Overall, the Abramtsevo Circle influenced several Russian modernist trends, such as theatricality, the notion of the overall unity of the artwork, and an emphasis on decorative arts, applied arts, and folk motifs.

Back to Top of Page

Sleeping Tsarevna

While similar to Western Art Nouveau, the Neo-Russian style was distinct in its integration of medieval Russian culture and folk traditions. Particularly important in this regard was Viktor Vasnetsov (1848–1926), who was originally associated with the realistic artists’ group called the Peredvizhniki (“The Wanderers”), but who then laid the groundwork for the Neo-Russian style by integrating motifs from Russian folk art, epics, and fairytales into his works.

Back to Top of Page

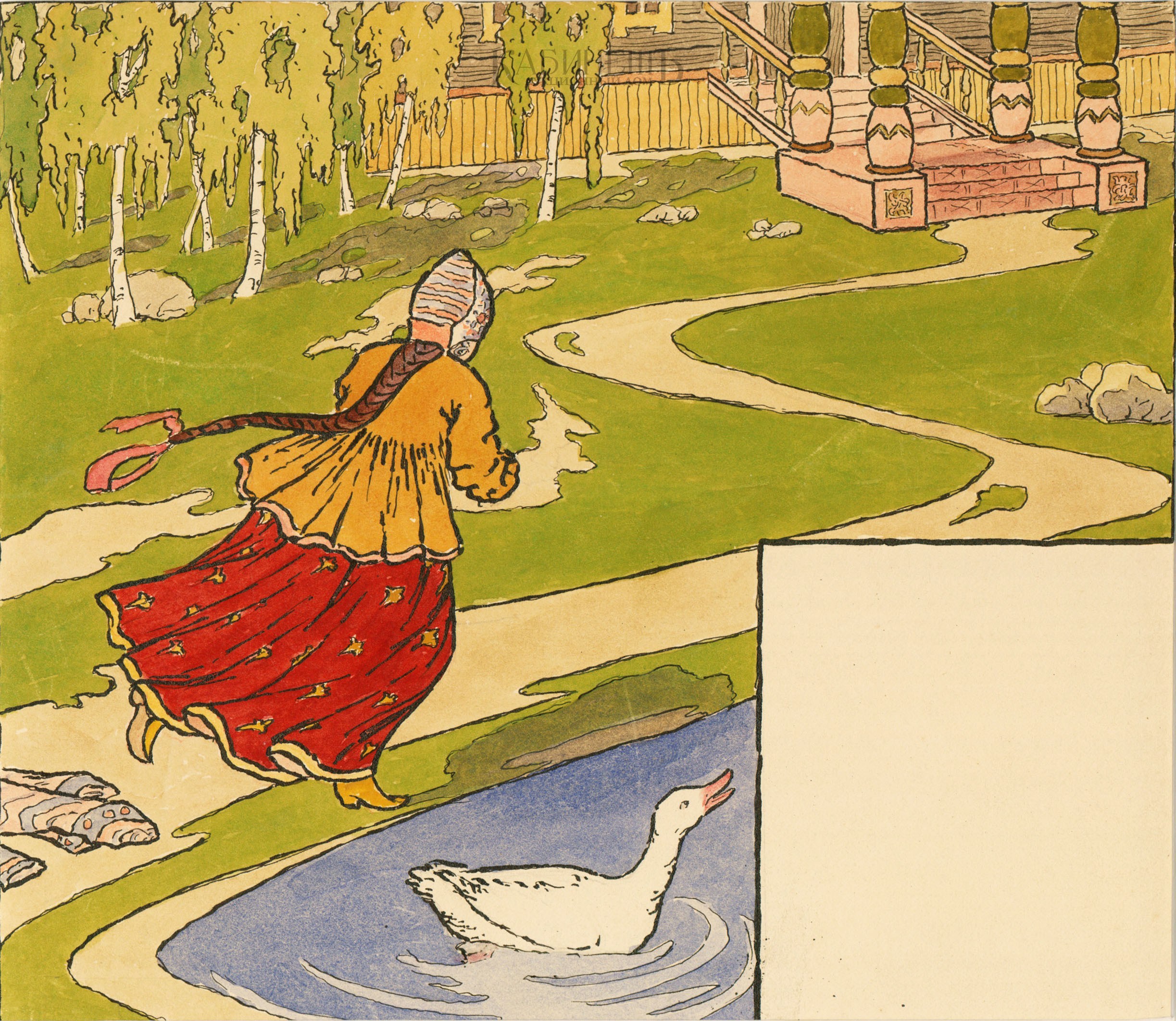

The Little White Duck

Most significantly for the history of children’s book design, the Abramtsevo Circle set the stage for the flowering of Russian book illustration and the incorporation of the Neo-Russian style into children’s books. In addition to Vasnetsov, another Abramtsevo figure seminal in the development of fin-de-siècle book design was the artist Yelena Polenova (1850–98). Her children’s book illustrations comingled realistic traditions with stylized folk-art ornamentation and a sense of the book as an integrated artistic object (Gesamtkunstwerk).

(On Abramtsevo and the Neo-Russian style, see Jackson 2007, 37–43; Paston 2014, 59–78; Rosenfeld 2014, 173–78.)

Back to Top of Page