“ROSTA Windows are something fantastic. It is a handful of artists serving, by hand, a huge nation of a hundred and fifty million. It’s instantaneous news wires remade into a poster….It is a new form introduced directly by life” —Vladimir Mayakovsky (in Barkhatova 1999, 134–35).

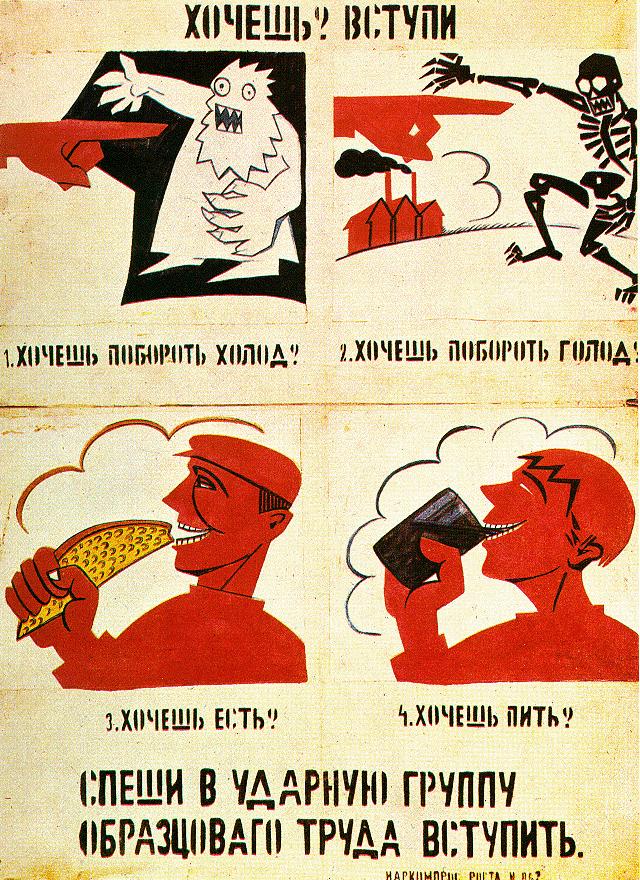

Do You Want To Eat?

One of the most colorful and significant examples of Soviet poster art in the Civil War era was the phenomenon of the so-called “ROSTA Windows,” i.e. informational posters that functioned as wall-newspapers, and were displayed in the windows of empty shops and in other busy urban places such as train stations and bridges. ROSTA was the acronym of the Russian Telegraph Agency (ROSsiiskogo Тelegrafnogo Аgentstva), a news agency that collected information by telegraph (ranging from government resolutions to breaking news from the front to propaganda aimed at the masses), and then distributed this information via published daily bulletins, wall-newspapers, and posters. One reason for choosing posters as a means of disseminating information was the poor state of the printing industry in this era. The ROSTA Window posters were hugely popular with the general public, and the opening of a new window was often attended by a huge crowd. The ROSTA artists worked together, sometimes through the night, to create posters at great speed, so that the news would not be out of date (White 1988, 65–67, 77–80, 114; Barkhatova 1999, 135–36).

The ROSTA Window posters were strongly influenced by advertising signs (вывески), folk art, and especially Russian lubki (illustrated broadsides): both consisted of boldly vibrant images, “whose color often spilled over the lines” (Povelikhina & Kovtun 1991, 153), accompanied by rhymed, often satirical, captions, and sometimes arranged in a sequence of frames. They were characterized by “laconicism, dynamism, expressiveness, and unusually sharp word and graphic combinations” (Barkhatova 1999, 135). Originally created in Moscow in Autumn 1919 by Mikhail Cheremnykh and the Russian Futurist poet Vladimir Mayakovsky, the ROSTA posters soon spread to other cities in the Soviet Union (White 1988, 1–3, 67, 81; Povelikhina & Kovtun 1991, 153; Kovtun 1996a, 185–86; Barkhatova 1999, 135).

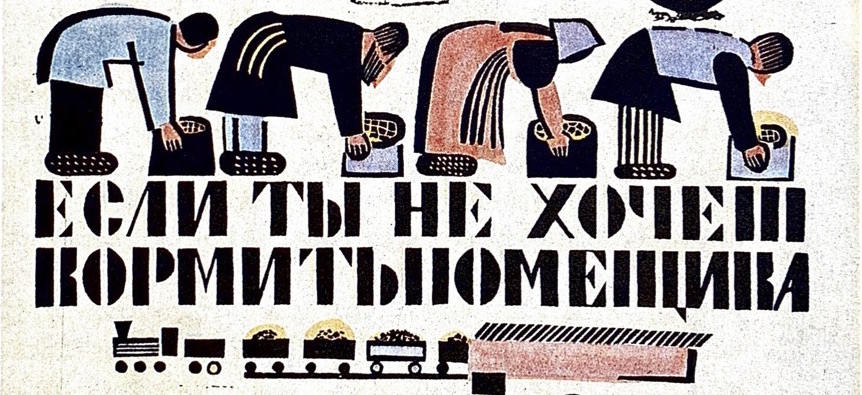

Worker's March

Established in April 1920, the Petrograd ROSTA Window department was headed by both Vladimir Kozinsky (1891–1967) and Vladimir Lebedev, and from the outset was quite distinct from Moscow. While the Moscow posters were created first by hand and then with cardboard stencils, in Petrograd the artists used linoleum engraving, and paid greater attention to color. They were also much bigger, created to fit the larger Petrograd shop windows. The Petrograd ROSTA Windows used “garish…and laconic images” that were viewed “as a unique graphic equivalent to those fresh social ideas which were agitating Russia’s revolutionary masses” (Barkhatova 1999, 137; White 1988, 67, 81–89).

Back to Top of Page

Ironcutting

Lebedev is widely considered to be the most important of the Petrograd ROSTA artists, and his posters actively engaged with avant-garde trends such as Cubism and Suprematism (Barkhatova 1999, 137; White 1988, 81–89). He created about 600 posters, although only about 100 survive to this day. Lebedev was also notable for the extreme speed at which he could work: “On receiving the latest telegram from the front or elsewhere, the theme for each Window would be chosen immediately . . . . Lebedev was able to produce an engraving in only seven minutes . . . . Otherwise there was a risk that the poster might be out of date by the time it had appeared” (White 1988, 85).

Back to Top of Page

Work with Your Rifle

Lebedev’s work for the ROSTA Windows laid the groundwork for some of his most innovative children’s book designs. For instance, the ROSTA poster You Must Work with Your Rifle Beside You (Работать надо, винтовка рядом, 1920) is dominated by boldly colored, flattened planes, and the worker is transformed into a faceless, geometrical shape. Bisecting the poster’s overall field, the worker’s body creates a diagonal that is paralleled by both the crosscut-saw and the stencil-style words (“You Must Work”), which form a line with the worker’s elbow. All three elements are in harmony as if equal: human arms, slogan, and saw.

Back to Top of Page

Ice Cream Vendors

The ice cream vendors in Lebedev’s children’s book Ice Cream (Мороженое, 1925) are similarly schematized and geometrized, their faces flat and featureless, their ice cream carts forming colorful diagonals across the page, while Marshak’s text celebrates the treat with a series of rhyming adjectives:

Delicious

Wild Strawberry

Beautiful

Pineapple

Birthday

Orange

Ice cream!

Отличное

Земляничное

Прекрасное

Ананасное

Именинное

Апельсинное

Мороженое!

This book also exemplifies Lebedev’s penchant for bright, bold colors. As Lebedev himself later said: “Color illustrations should be intensely colorful as well as precise and concrete. But the intensity should come not from gaudiness, but from the painterly composition” (Lebedev 1933).

(Find a more detailed analysis of Ice Cream in the next essay.)

Back to Top of Page

Workers as Patterned Rows

One prominent characteristic of both Lebedev’s avant-garde poster design and children’s book illustration is his penchant for creating rows of repeated, almost identical figures, as seen in a ROSTA poster from 1920: Peasant, If You Don’t Want to Feed the Landlord, Feed the Front… (Крестьянин, если ты не хочешь кормить помещика, накорми фронт..., 1920), and in an image from his children’s book Yesterday and Today (Вчера и сегодня, 1925). Lebedev’s ornamental rows of repeated figures can been likened both to old and new styles; they resonate not only with abstracted, Suprematist patterns in Soviet textiles and porcelain, but also to more traditional, ornamental designs in Russian folk art: the “row of young Russian peasant women with water-carrying yokes resembles an ornamental border on peasant’s embroidery” as well as “Suetin’s Suprematist designs for textiles” (Rosenfeld 2003, 212 & 245).

(Find a more detailed analysis of Yesterday and Today in the next essay.)

Back to Top of Page