“The Russian children’s picture book is the best in the world” (Русская дошкольная книга—лучшая в мире)—Marina Tsvetaeva (1931/1979, 2:313)

Colorful Geometry

Lebedev’s illustrations for his books with Marshak in the 1920s are particularly effective in their application of diverse avant-garde techniques to both the children’s book and the new Soviet reality. His flattened, abstracted planes, geometrical shapes, and vibrant colors share an affinity with artistic trends of the previous decade, including the “geometrization” and “bright hues” in Kazimir Malevich’s Cubo-Futurist works of 1912 (Néret 2003, 25–29), as well as Malevich’s later Suprematist works. Lebedev’s work also evokes El Lissitzky’s mélange of Suprematist abstract “planar rhythms” and the Constructivist emphasis on architecture and “axonometry” (Rosenfeld 2003, 174–93), which Railing calls a “Suprematism of typography” (1991, 38). Lebedev’s emphasis on diagonal forms, meanwhile, echoes the early twentieth-century Russian-Soviet avant-garde overall, for whom “the new archetypal symbol of unstable, fickle existence . . . was the diagonal” (Steiner 1999, 63). (Read more about Lebedev’s use of the Constructivist diagonal in this section of the Production Book Essay.)

Back to Top of Page

A Singular Cubism

Yet, although Lebedev was acquainted with many members of the radical avant-garde in the 1910s and 1920s, and was influenced by diverse sources such as Russian folk art, lubki (illustrated broadsides), Cubism, Suprematism, and Constructivism, he never officially joined any of the artistic circles of the day, instead developing his own path. Lebedev later said that he considered himself “an artist of the 1920s”: “I created my best works then . . . . The roots of all my ideas grew from that era . . . and the language of my art was Cubism.” Yet Lebedev adapted Cubism to his own individual style: “I’m not an imitator; I start with nature and my own understanding of the world, and my Cubism does not resemble the Cubism formulated by the theoreticians” (quoted in Petrov 1971, 248).

Back to Top of Page

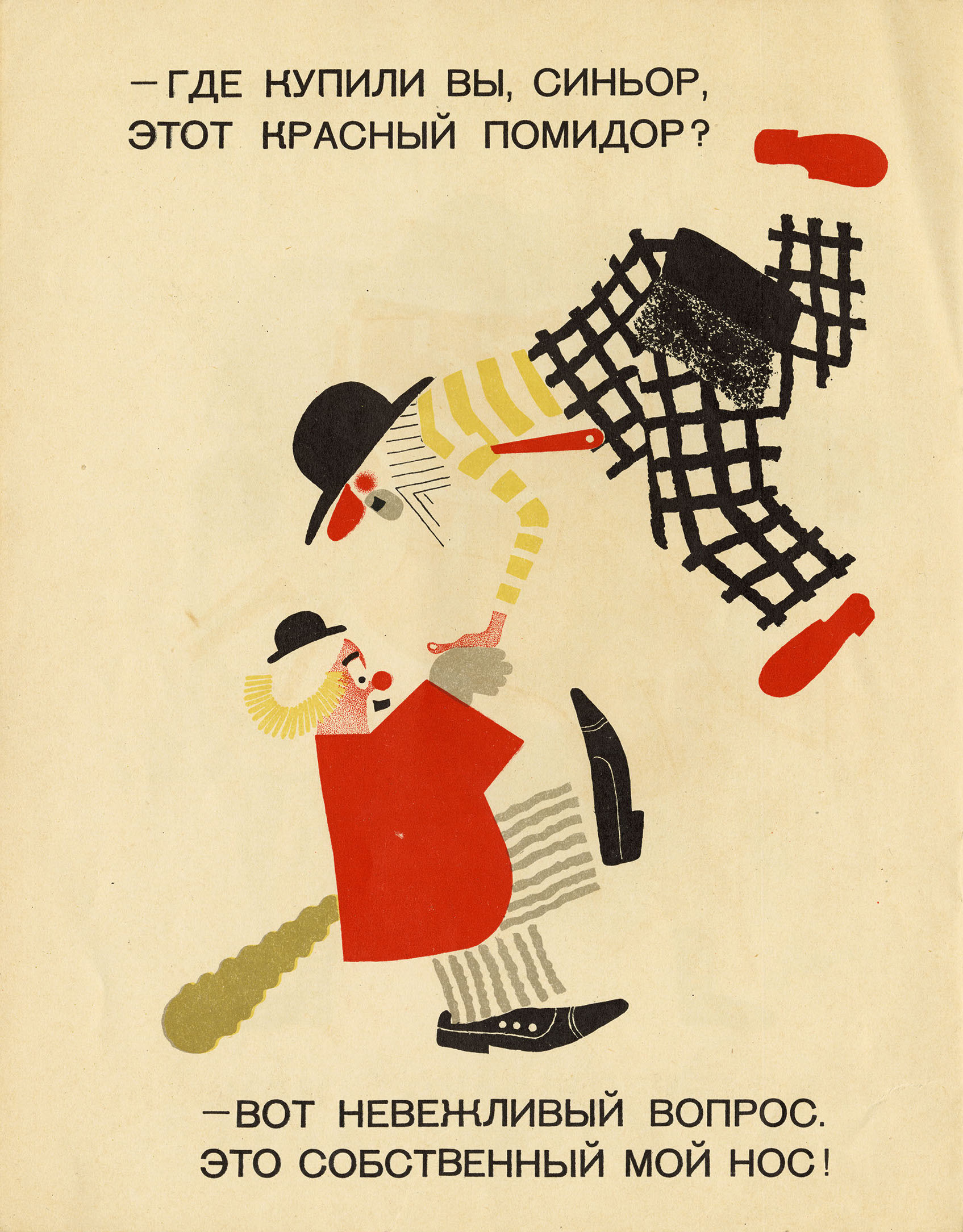

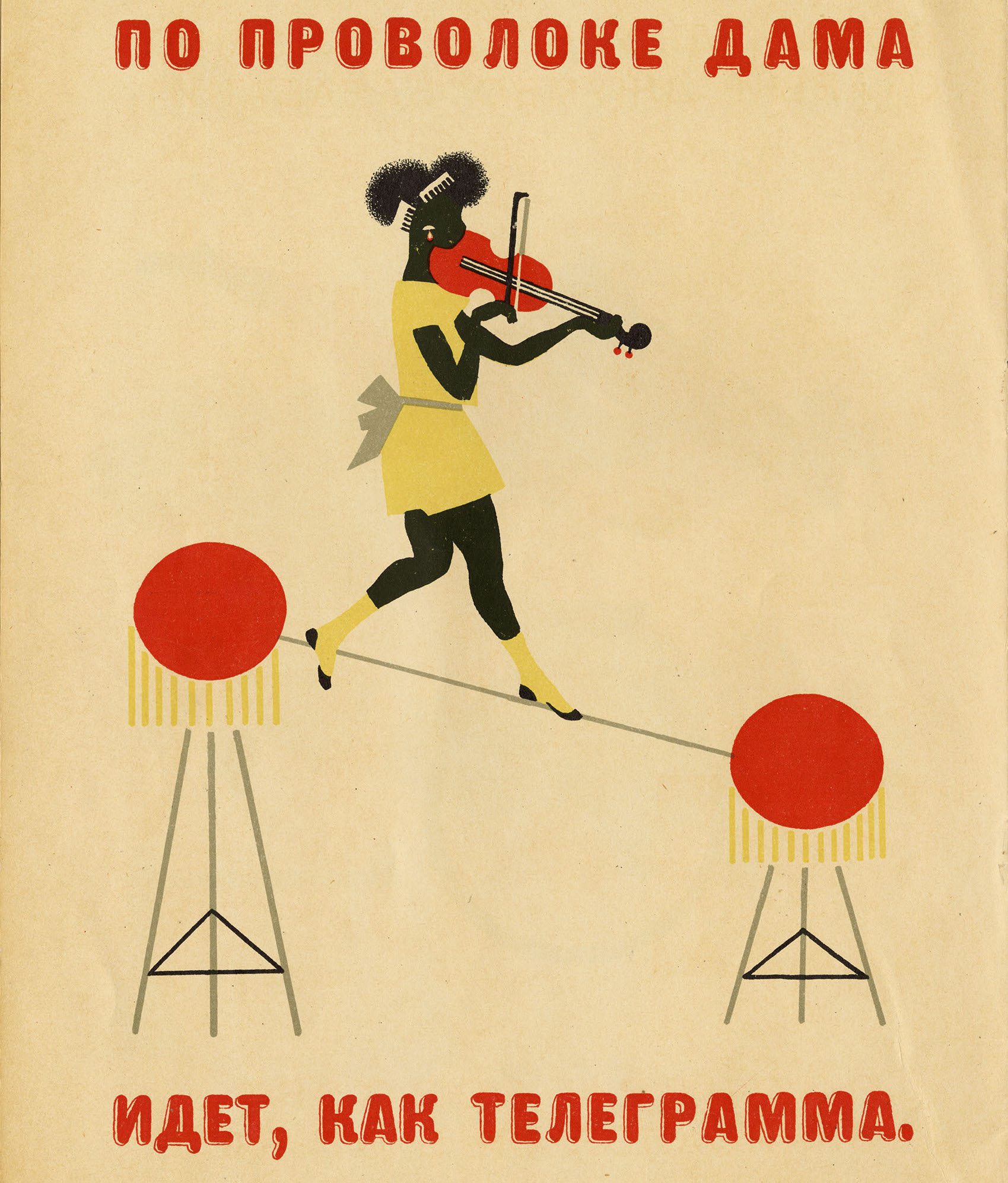

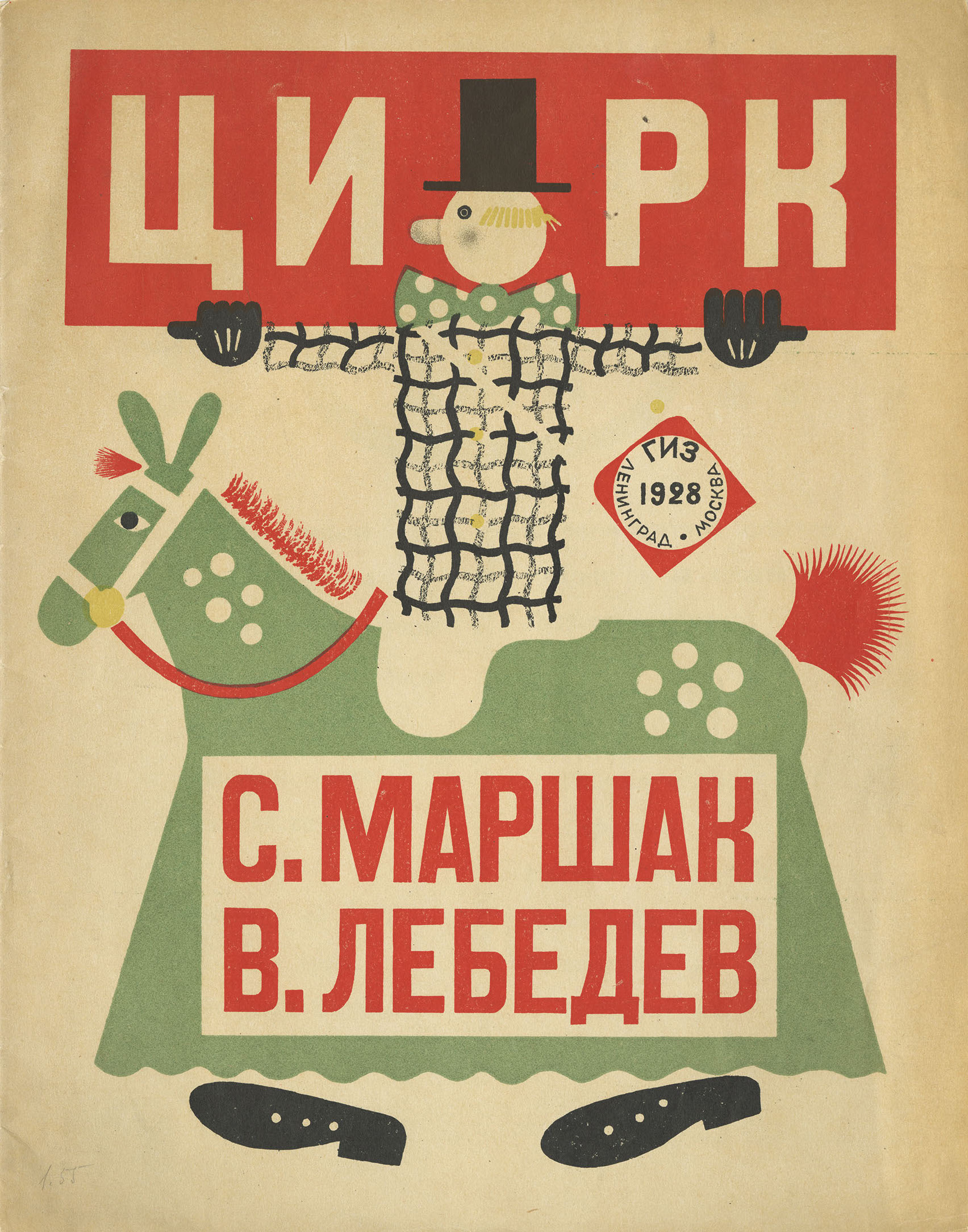

The Circus (Цирк, 1925), the first collaboration between Marshak and Lebedev, is often cited as one of their most innovative achievements. As is the case for most of their collaborations, the text is in rhymed verse. Marshak later recalled that Lebedev first created the drawings, while Marshak wrote the text afterwards to accompany them: “For Circus . . . I wrote poems that were like signatures to Lebedev’s drawings” (Marshak 1968–72, 1:513). Lebedev is known to have had a special interest in the Leningrad circus; he often sketched circus performers during rehearsals (Rosenfeld 2003, 208). The relationship between image and text is particularly vibrant in The Circus: Marshak’s “witty lines” play an important role in the visual composition of each page, “framing the lithographs from above and below” and endowing each page with vital equilibrium (Fomin 2009b, 2:13).

Back to Top of Page

Page 6 of The Circus contains the line often praised by the famous Futurist poet Vladimir Mayakovsky. Translated with literal word order, it reads: “Along the wire the lady / Walks like a telegram.” The playful rhyme of “lady” (dáma) and “telegram” (telegrámma) provides a bouncy accompaniment to the brightly colored geometric shapes of Lebedev’s illustration. Both image and text advertise their rapid modernity: Marshak’s choice of the word “telegram” heightens the sensation of speed, as does Lebedev’s image of the slender wire, a dynamic diagonal line zipping down the page from one red circle to the other. The tightrope walker is balanced with precarious symmetry between two red balls teetering atop spindly triangular stands, which also evoke modernity in their resemblance to radio towers. Image and text intersect here in that the balls function as gargantuan punctuation points, marking the start and finish of the circus-lady’s journey, while also echoing the period that ends Marshak’s text.

The bold red palette of this page (in both image and text) evokes the lubok (illustrated broadside)and the icon, both of which privileged the color red along with other bright hues (White 1988, 5; Alekseeva 1996, 11).

Back to Top of Page

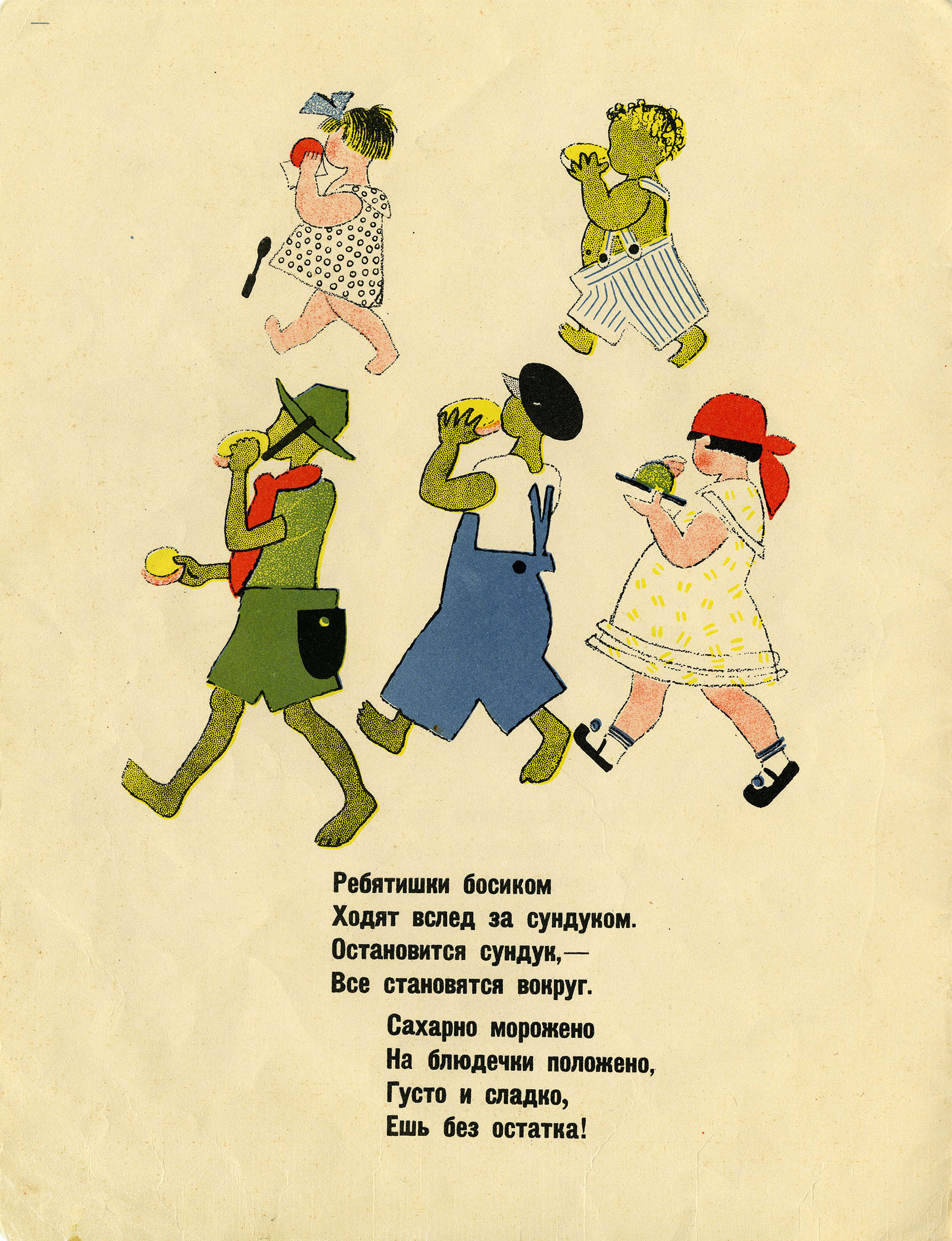

While exhibiting innovative avant-garde visual designs, Marshak and Lebedev’s collaborative works also point to the ideological concerns of their era. Ice Cream (Мороженое, 1925), for instance, juxtaposes a group of children longing for ice cream with a gluttonous fat man, who represents an overbearing capitalist, as was the case in numerous works in that era (Weld 2018, 98–107). Page 8 depicts the fat man exploding with greed: “But the fat man doesn’t stop, / He gets right down to work. / Grabbing an entire cup, / He tosses it down his throat.” The details of his clothing, such as his gold watch chain and spats, underscore his symbolic embodiment of bourgeois, capitalist wealth. He is so unable to contain his unbridled greed that he eats up all the ice cream and turns into an enormous snowdrift.

Weld notes that, alongside the contemporary Soviet context of this poem, the gluttonous fat man also evokes a medieval carnivalesque ritual in which the “clown disguised as king” is dethroned by a “victorious collective of children,” which “restores order and justice to the world” (2018, 100–104). Many scholars suggest that the fat man represents not only the greedy bourgeoisie in a general sense, but also the Soviet NEP-men, i.e. capitalist entrepreneurs who took advantage of Lenin’s New Economic Policy in the 1920s (Rosenfeld 1999b, 176; Hellman 2008, 222). Yet Fomin persuasively argues that the fat man in Ice Cream still contains a “pithy expressiveness,” his metamorphosis from man to snowdrift driving the plot in a way that is “not just amusing, but also poignant” (2009b, 2:13).

Back to Top of Page

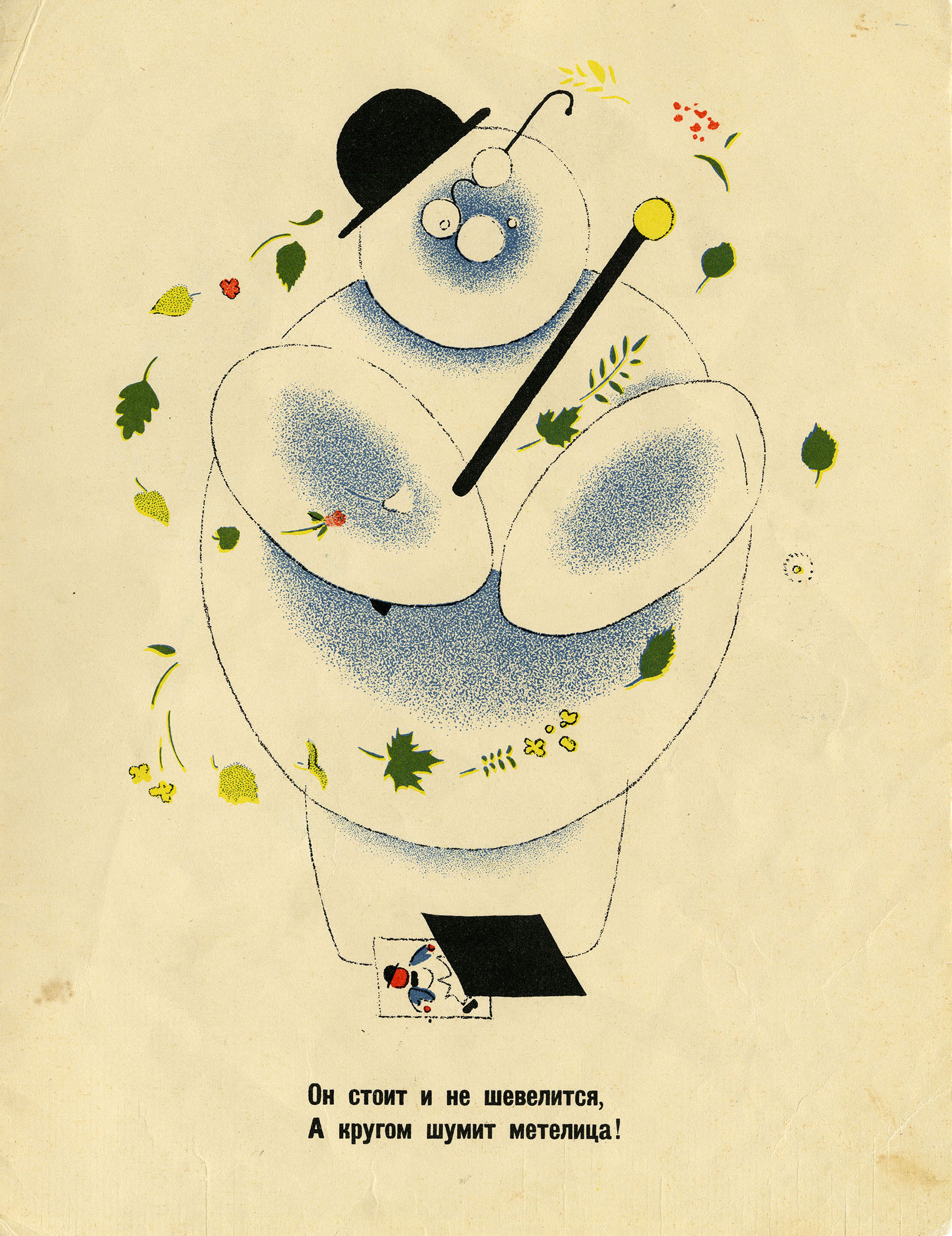

In fact, on page 11, the fat man, now a snowman in harmony with nature, is depicted with a gleefulness that seems more whimsical than vindictive. Both text and images are playful, with Lebedev’s leaves and flowers gently swirling in the breeze around the snowman, whose glasses are now humorously askew, while Marshak’s lighthearted text emphasizes the almost four-syllable rhyme of shevelitsiá (budge) and metelitsá (snowstorm): “He stands and doesn’t budge, / While all around, a snowstorm howls!” At the same time, this book powerfully exemplifies Lebedev’s adaptation of avant-garde techniques to the children’s book. Many of the characters are depicted with schematized, geometric forms that evoke both Malevich’s works and Lebedev’s own posters for the ROSTA Windows. (Read about the relation between Ice Cream and the ROSTA Window posters in the previous essay.) Rosenfeld also suggests that Lebedev’s faceless human figures recall the “robotlike figurines” that El Lissitzky created for a version of the Futurist opera Victory Over the Sun, produced by Malevich’s followers in 1920 (2003, 211).

Back to Top of Page

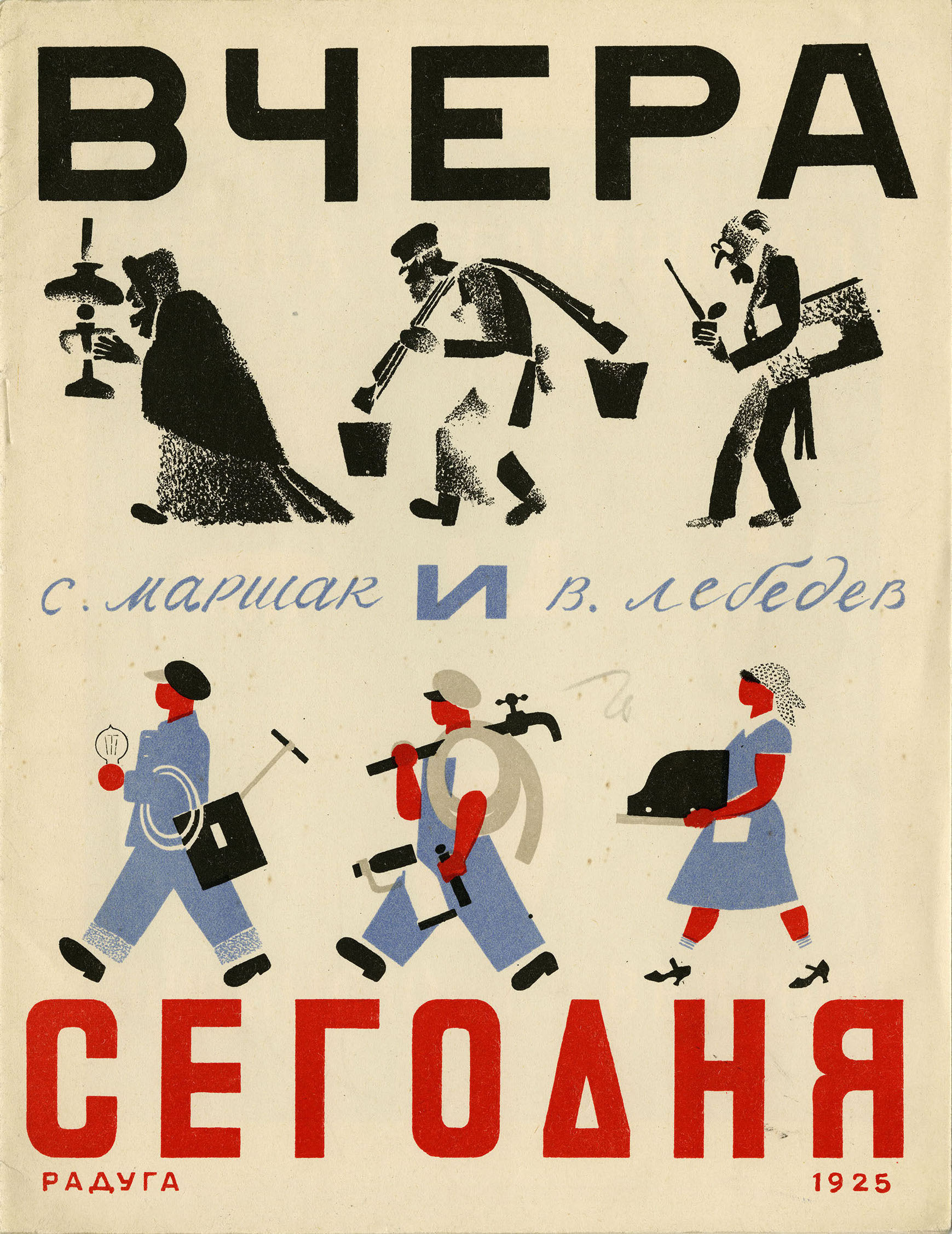

Ideological concerns, and the relation between image and text, become particularly complex in Yesterday and Today (Вчера и сегодня, 1925), which juxtaposes old objects and customs with twentieth-century inventions. Intriguingly, there is a disconnect between the message of this book and its actual effect. While Lebedev’s bold cover declares its sympathy for the side of the new, with its line of bent, aged figures carrying outdated objects, contrasted to young, strong figures heralding the new things, one can observe a tension between the soulfulness of Marshak’s text (suggesting a sympathy with the antiquated, no-longer-needed objects) and the modern optimism of Lebedev’s illustrations. In Marshak’s autobiography of his early childhood, he remarks on some of the objects of this poem with tender poignancy, suggesting that the transition from old to new was not always straightforward: “Nearly all my childhood was spent by the light of a kerosene lamp . . . . Those years marked the junction between the last century and the present one. The past was still fully alive, and did not seem to be making ready to cede to the new” (1964, 40).

Back to Top of Page

Indeed, this tension between old and new is not only located in the text; even in Lebedev’s illustrations one finds a contradiction between the antiquated technology and the poetic sympathy underlying its depiction. On page 1, several of the main “characters” are introduced: “Kerosene Lamp; Stearin-Wax Candle; Yoke with Bucket; Inkwell with Fountain Pen.” Yet, perhaps some irony lies in the contrast between the archaism that these objects represent and the modernity of their artistic depiction. They float in a field of bright blue, unanchored by context or a mimetic frame. “The Soviet illustrator learned to place a protagonist’s activities in a kind of empty space…. Perhaps the most obvious stylistic transformation in Soviet children’s books revolves around the appearance…of the blank spaces that typically surround a book’s principal ‘action’ ” (Bird 2011, 12). In this case, the antiquated, overbearing yoke and bucket, symbols of peasant oppression, anchor the page with spare, flattened symmetry. Just above them, the inkwell, rather than representing a dusty past, is represented as a modern, geometrized object, its parts evoked with the mathematical precision of perfect rectangles and a circle.

Back to Top of Page

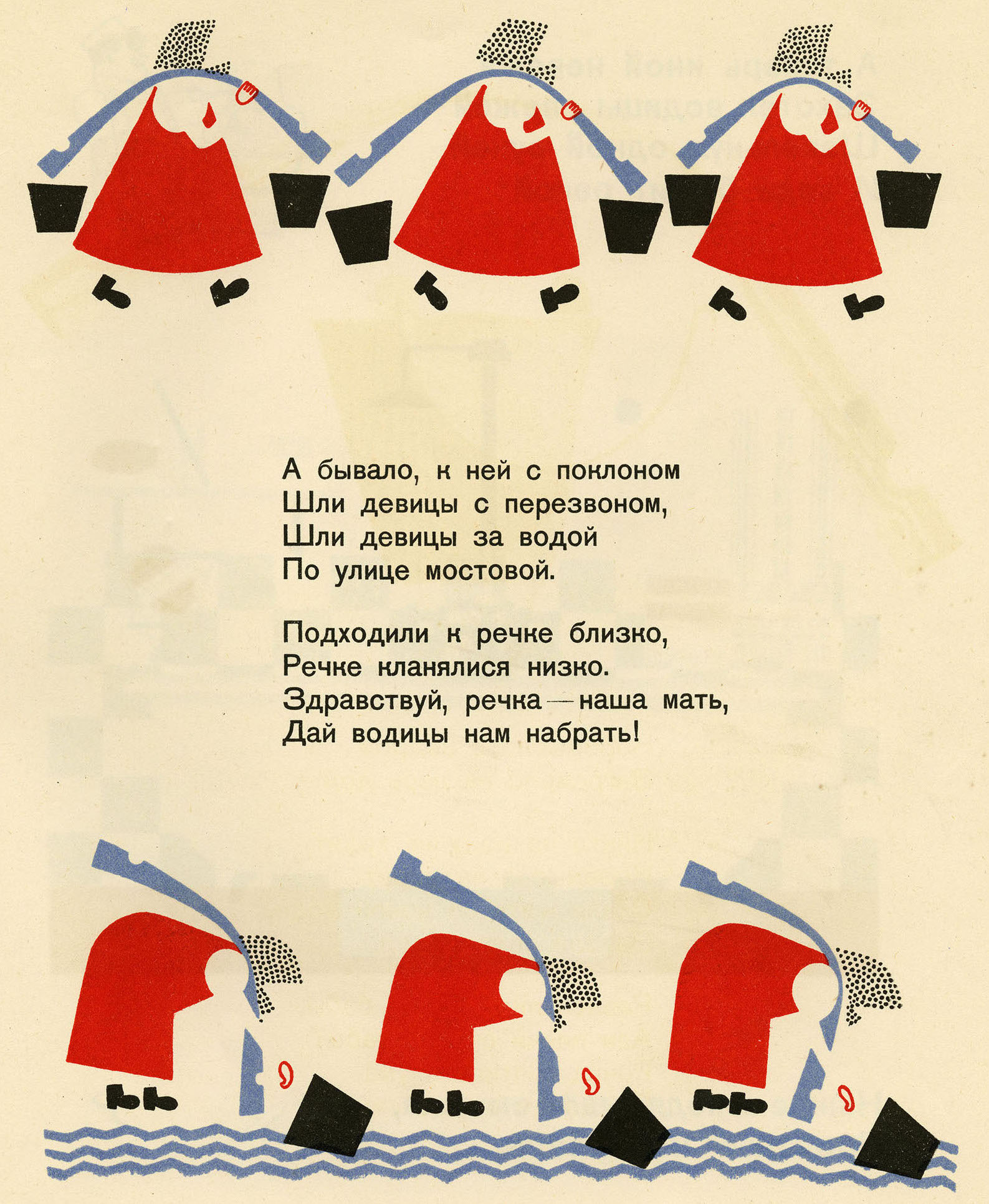

Even more striking is the contrast between the past and the present on pages 11–12, which juxtapose an image of young girls fetching and carrying water from the river with an image of a young “lout” (невежа) using a faucet with running water. On page 11, the repeated image of girls from the olden days creates a rhythmic, visual pattern, like a Greek chorus commenting on the text. They are flattened and stylized, without any facial features, their heads rendered as pointillist dots that evoke the silhouette of their kerchiefs, their feet mere shapes kept at a distance from the rest of their bodies. The image evokes both Lebedev’s own ROSTA posters and the Suprematist designs created by other members of the avant-garde (as discussed in the the previous essay).Yet, in this simplified, “Suprematist” depiction of young women going to the river, Lebedev creates a visual poetry that is deeply sympathetic to them; they seem as alive and resonant, if not more so, than the “lout” using water from his bathroom sink on page 12. The text on page 11 heightens this perception:

In the old days, with a reverent bow

The girls approached the river,

Their buckets ringing,

As they walked on the cobblestone path.

А бывало, к ней с поклоном

Шли девицы с перезвоном,

Шли девицы за водой

По улице мостовой.

When they arrive at the river, they bow down low and greet her with reverence as they would Mother Nature:

They walked up to the river’s edge,

Bowed down low to her:

“Hello, Mother River

Let us draw water from you!”

Подходили к речке близко,

Речке кланялися низко.

Здравствуй, речка — наша мать,

Дай водицы нам набрать!

Nothing in either text or illustration undermines the poetically intense connection between the young girls and Mother River, whereas the lout washing himself at the sink seems both silly and pompous.

Back to Top of Page