“The child will quickly forget the content. But the illustration—its range of colors, its design—might forever leave a trace on the child’s soul” —Joseph Knebel (quoted in Iuniverg 1997, 117)

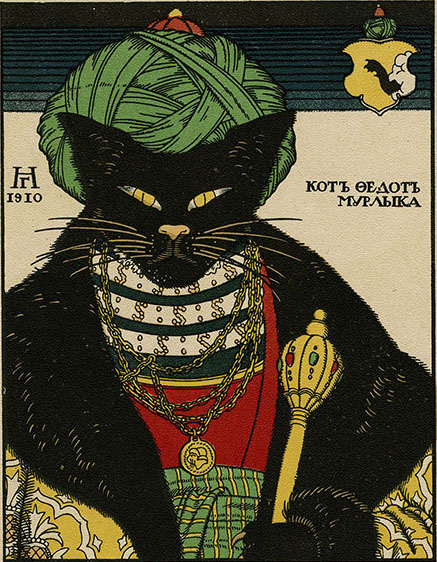

The Cat Kotik Fedot Murlyka Surveys the Universe

One of the most important publishers of Russian picture books was Joseph (Iosif) Nikolaevich Knebel (1854–1926), who produced a series of lavishly illustrated books for children called the “Gift Series” (Подарочная серия) in the early years of the twentieth century.

Several of the works from the “Gift Series” are in the Harer Collection of Russian Books.

Joseph Knebel (Йосиф Николаевич Кнебель) was from a German-speaking Jewish family in the city of Buchach, one of the oldest Jewish centers of Galicia, then part of the Austro-Hungarian empire (now in present-day Ukraine). After spending several years in Vienna, where “he dreamt about working in the book business” (Iuniverg 1989, 5), Knebel moved to Moscow in 1880, and founded a bookstore there with Pavel Grossman in 1882. After Grossman’s death in 1890, Knebel became the sole proprietor, although the firm retained its original name, “Grossman and Knebel,” at 13 Petrovskie linii (Iuniverg 1997, 9–31).

Knebel’s publishing firm was the first in Russia to specialize in the fine arts, and was also “the first Russian publisher to understand the importance of book design in works oriented toward small children” (Rosenfeld 2014, 173). Knebel was also a strong advocate for children’s art education. He pioneered the idea of “Art in the Schools” and published many publications aimed at teaching children about art (Iuniverg 1997, 9–31).

The Gift Series

From 1906 to 1918, Knebel produced about fifty books overall for the “Gift Series,” whose topics included Russian folktales, fables, and literary fairytales, as well as numerous foreign tales (translated from Arabic, French, Swedish, and other languages). Each book in the “Gift Series” was twelve pages long and nine inches wide by twelve inches high; each was priced at fifty kopecks and contained numerous full-page color illustrations (Iuniverg 1997, 115–17).

Back to Top of Page

“In the ‘Gift Series,’ . . . luscious, festive colors, flawlessly produced in the illustrations, are successfully combined with expressive typefaces and the unusual texture of first-class paper . . . . It is clear why so many of these books have entered the golden treasury of Russian book illustration and have been loved ever since not only by children but also by bibliophiles” (Iuniverg 1997, 113; on the “Gift Series” overall, see 113–43).

Alexandre Benois, a leader of the Mir Iskusstva (World of Art) group, later said that a Knebel publication was as much of an “event” as a new art exhibit, and that Knebel’s books exemplified the “Renaissance” of the Russian book at the turn of the century (quoted in Iuniverg 1997, 140).

Back to Top of Page

For his “Gift Series,” Knebel hired “the best graphic artists of the period” (Rosenfeld 2014, 173). In fact, he viewed the illustrations as more important than the content: “The most important figure in Knebel’s children’s books was the artist, not the writer” (Iuniverg 1997, 117).

In a letter to Dmitry Mitrokhin, Knebel made his priorities clear: “Ideally, aim for greater simplicity in the plot . . . and create brighter, more colorful illustrations, if possible, covering the entire page, nothing but colors” (quoted in Iuniverg 1997, 117).

Back to Top of Page

The Knebelists

Two of the most significant illustrators working with Knebel for the “Gift Series” were Georgy Narbut and Dmitry Mitrokhin, whose works can be found in the Pamela Harer Collection. They were both members of the younger second generation of the Mir Iskusstva group (“The World of Art”) and began exhibiting with Mir Iskusstva around 1910.

“Narbut and Mitrokhin first came into their own as illustrators of children’s books for Knebel’s publishing house. At that time they were simply called ‘Knebelists,’ which usually signified [creators of] books of excellent quality and artistic taste” (Iu. Pimenov, quoted in Iuniverg 1979, 6). Both Narbut and Mitrokhin were particularly interested in typography and the printing process, and they collaborated closely with Knebel’s printer, the Printing House of R. Golike and A. Vil’borg (Iuniverg 1997, 136).

See the books by Dmitry Mitrokhin and Georgy Narbut digitized for this exhibit.

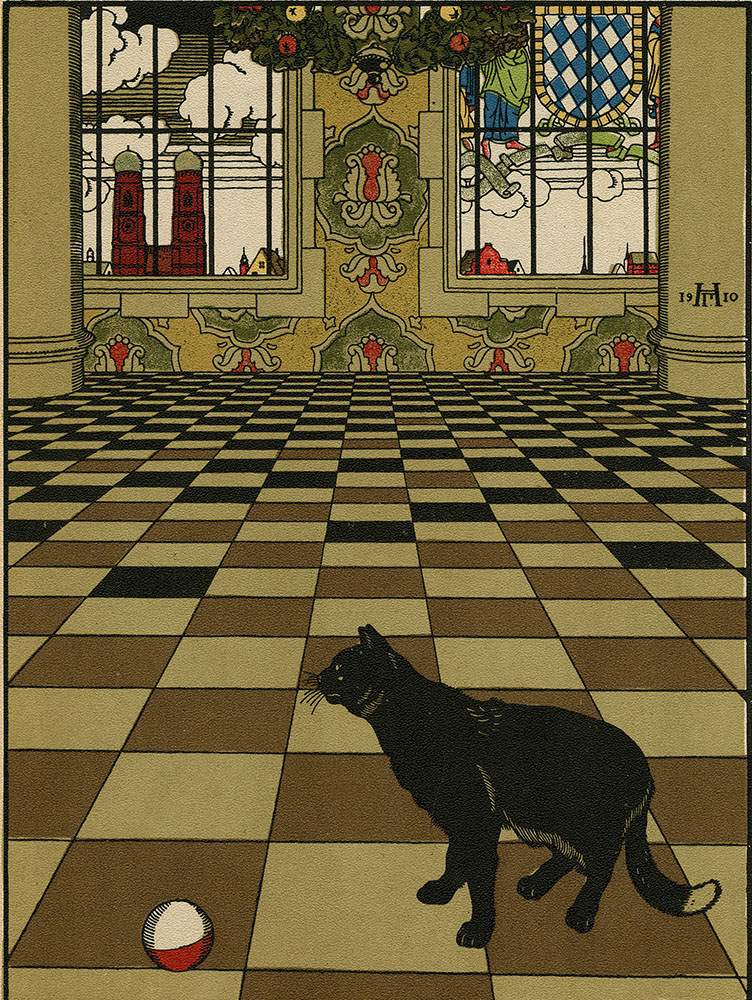

Back to Top of Page

Georgy Narbut (1886–1920) was born in Ukraine. He started collaborating with Knebel in 1909 and illustrated twelve books for the “Gift Series.” His early works show the influence of his mentor, Ivan Bilibin, as well as his interest in folk motifs, heavy contours, and flattened planes (Lemmens & Stommels 2009, 63). His work was influenced by a vast range of sources such as lubki (illustrated broadsides), Japanese woodcuts, icons, medieval engravings, chinoiserie, and peasant toys (Rosenfeld 2014, 180). Overall his style tended toward “a minimum of text and maximum of visual imagery” and often involved the transformation of objects into an “elegant ornamental arabesque” (Rosenfeld 1999d, 92). Narbut was particularly interested in the printing process and saw himself as a collaborator with the printer. Iuniverg argues that this focus helped produce Narbut’s characteristic “precision, brightness, and sparseness of color tones” (1997, 128–29).

Two of Georgy Narbut’s books are in the Harer Collection:

War of the Mushrooms (Война грибов, 1909), and How the Mice Buried the Cat (Как мыши кота похоронили, 1910).

Back to Top of Page

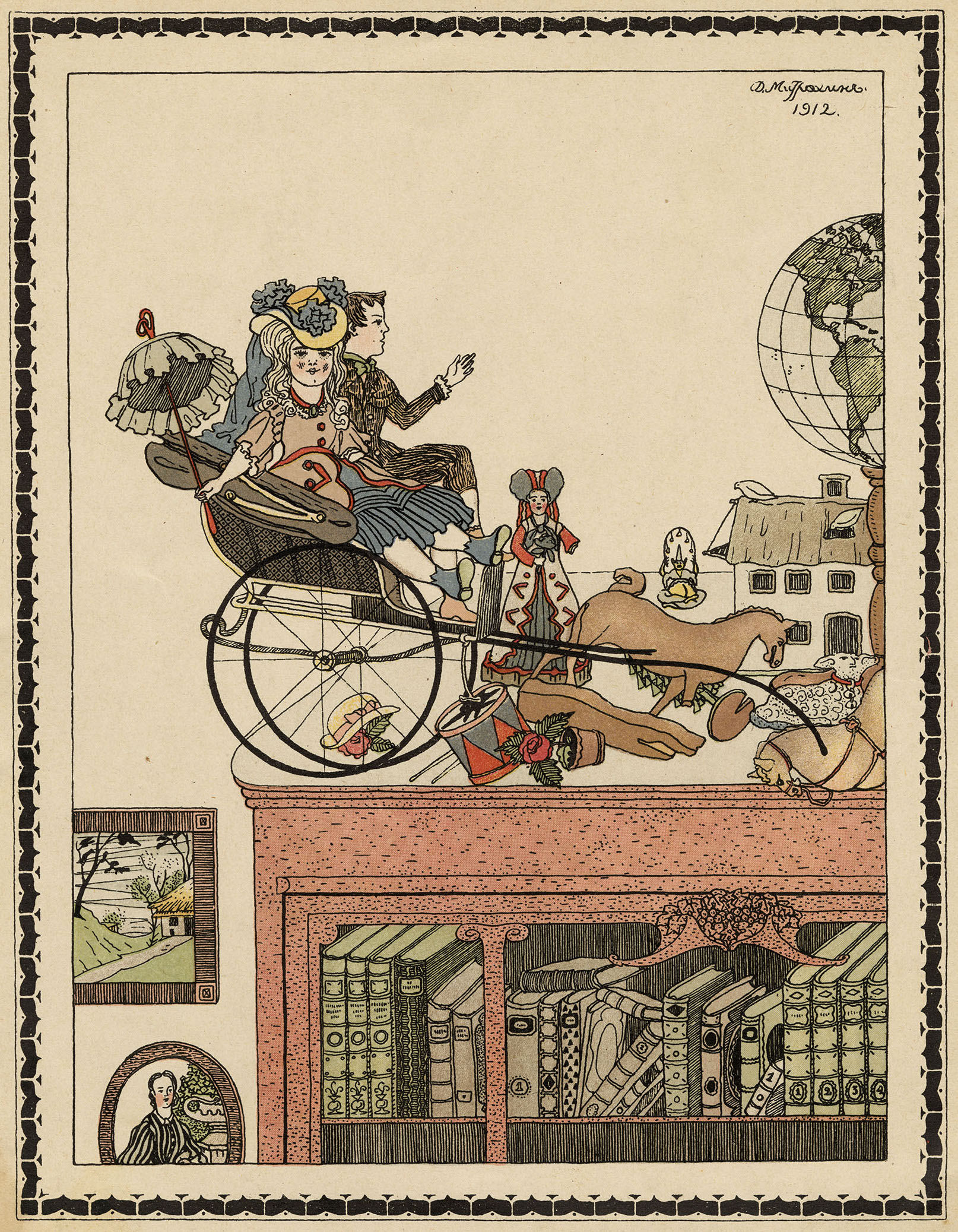

Dmitry Mitrokhin (1883–1973) was influenced by diverse sources such as Art Nouveau, Aubrey Beardsley, Japanese prints, and lubki (illustrated broadsides). He “masterfully combined fantastic subjects with realistic documentary details” (Rosenfeld 1999d, 95). Mitrokhin particularly specialized in all the different elements of book design, such as book covers, endpapers, vignettes, and typography, and his works embodied the “World of Art view of the printed edition as a work of art in which all the components must be in harmony” (Pliusnina 1999, 57). Mitrokhin later said: “Throughout my long life, I’ve concerned myself first and foremost with book illustration . . . . Sketches and drawings from nature have always been the basis of all my work. You have to see before you can draw; the more you sketch from nature, the easier it will be to depict something imagined, read, or heard” (quoted in Rosenfeld 2014, 182).

Three of Dmitry Mitrokhin’s books are in the Harer Collection, two of which are from Knebel’s Gift Series: Papa's Globe (Земной глобус папы, 1913), and The Life of Almansor (Жизнь Альмансора, 1913).

Back to Top of Page

Knebel’s “Gift Series” reflected a broader worldwide trend in children’s book publishing in this era, in which a new emphasis on illustrations over content had emerged. In Russia the artists of the Abramtsevo Circle (especially Yelena Polenova) espoused this approach, emphasizing decorative elements and folk motifs more than literary content. Ivan Bilibin and others further elaborated this trend, producing lavishly illustrated, large-scale books, and Knebel adopted that approach with particular success (Iuniverg 1997, 115–17; Lemmens & Stommels 2009, 61).

Similar trends occurred in the West. We have already seen that Walter Crane and other artists of England’s “Golden Age” emphasized the notion of the book as an overall unity and a work of art in its own right. Soon thereafter, advances in the technology of color printing ushered in an era of luxurious British children’s books, and “illustration was briefly elevated to the status of fine art” (Hearn 1996, 22). Illustrators such as Arthur Rackham (1867–1939) and Edmund Dulac (1882–1953) flourished at this time, producing lavishly illustrated editions. For the Anglo-American audience, this period still has a particularly strong resonance, as Lerer aptly notes: “Edwardian England . . . live[s] in our memories as gilt-edged times of childhood taste” (2008, 254). Knebel’s publishing house embodied the Russian equivalent of those Edwardian-age children’s book illustrators.

Back to Top of Page