“The great artistic-aesthetic experiment of the 1920s . . . found perhaps its fullest, most clearly articulated expression in the art of illustrating and designing children’s books” (Steiner 1999, 175)

The Children’s Book as a Forgotten Weapon

Immediately after the Russian Revolution in 1917, children’s literature and education emerged as an object of great concern and debate in Russia. The project of influencing the young next generation became an essential component of creating a new society. In the oft-cited words of Leonard Kormchy, children’s literature was a “forgotten weapon” that should be deployed in the revolutionary struggle against the bourgeoisie (1918). Nadezhda Krupskaya (Lenin’s wife, who exerted a great deal of influence before and after his death, and served as Deputy Minister of Education) also spoke of children’s literature as “one of the mightiest weapons in the socialist education of the new generation” (quoted in Balina 2008b, 4).

Yet, as Balina points out, these debates about the role of children’s literature in society were not new: such discussions can be traced back to the early nineteenth century, when “pedagogical merit” was often considered more important than “artistic value.” In fact, she argues, the “ideological agenda imposed on Soviet literature was hardly a creation of the Soviet propaganda system” since critics such as Vissarion Belinsky (1811–48) and Nikolai Dobrolyubov (1836–61) viewed the notion of ideinost’ (“ideological content”) as an essential component of literature, sometimes “its first and foremost value” (2008b, 3–4).

Childhood as a Means of Imagining Revolutionary Transformation

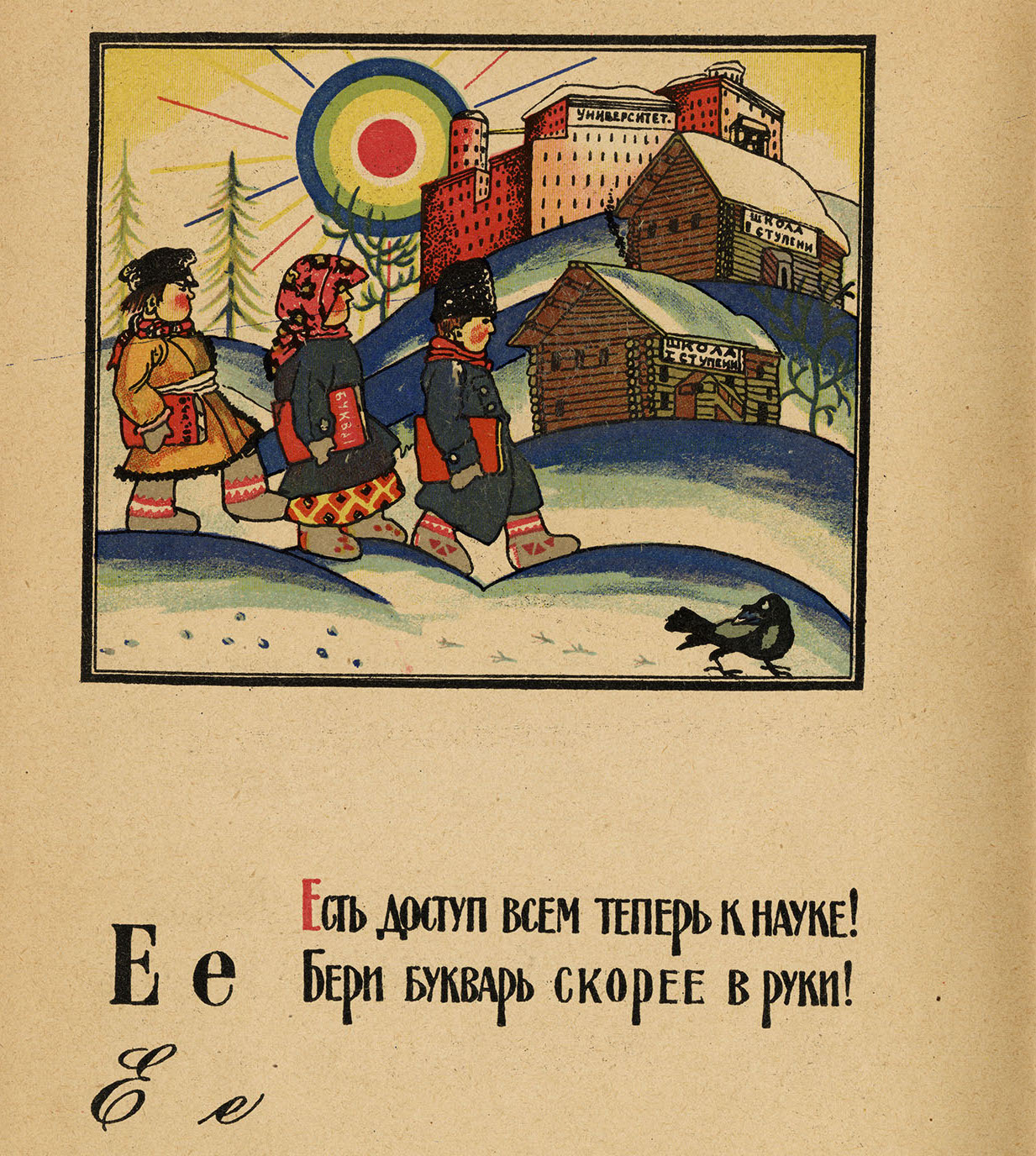

Nonetheless, children emerged as a focal point in the early years of the Soviet Union: “Childhood functioned as a means of imagining revolutionary transformation,” and the Bolsheviks viewed children “as ‘embryonic’ collectivists, the . . . bold constructors of the revolutionary future.” In 1918, Lenin himself declared: “It is mandatory that we exclude from our education the abundance of dead knowledge that the old school provided,” and early on education was seen as a means to propagate the ideas of “collectivism, internationalism, and class solidarity” (Kirschenbaum 2000, 1–2; Balina 2008b, 5).

In the immediate aftermath of the Revolution, during the period of Civil War and “war communism,” Russian society overall underwent great deprivations. At this time the publishing industry went into a period of deep decline. Yet this began to change markedly by 1921: “The abandonment of the economic and political restrictions of the ‘war communism’ of 1918–21 turned children’s literature into a fast-growing section of the publishing industry” (Oushakine 2016, 164). The People’s Commissariat for Education, led by the influential figure Anatoly Lunacharsky, established an “Institute for Children’s Reading” in 1921, and the Soviet children’s book became an arena where readers could be clearly molded and guided towards a new set of ideals (Lemmens & Stommels 2009, 83–84; Maguire 1968, 5–7; Fitzgerald 1970; Sokol 1987–88, 8).

The Golden Age of the Avant-Garde Children’s Book

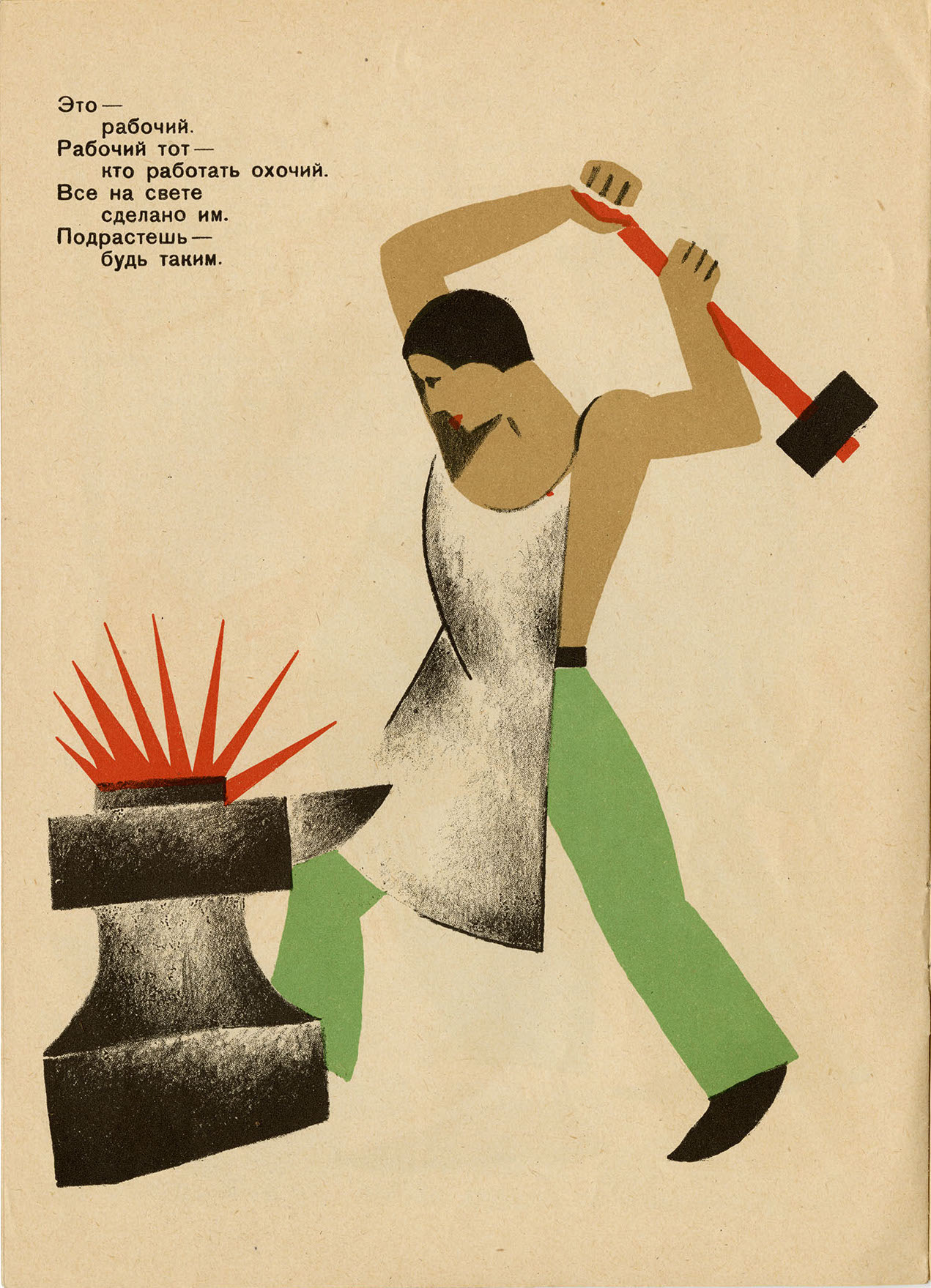

By 1924, the Communist Party had declared that one of its principal new objectives was “to create a children’s literature under the strict control and supervision of the party, with a view to fostering a stronger sense of class-consciousness, international solidarity, and love of work” (quoted in Hellman 2013, 304). However, in the 1920s an unlikely disjunction existed between the Party emphasis on ideologically correct themes and the simultaneous allowance for formal experimentation (Balina 2008b, 8–9), which ironically allowed for the emergence of a golden age of avant-garde children’s book design. “Our fascination with Soviet graphic art of the 1920s and 1930s is at least partly explained by its mystifying combination of oppressive social policies and exuberant artistic imagination" (Bird 2011, 25).

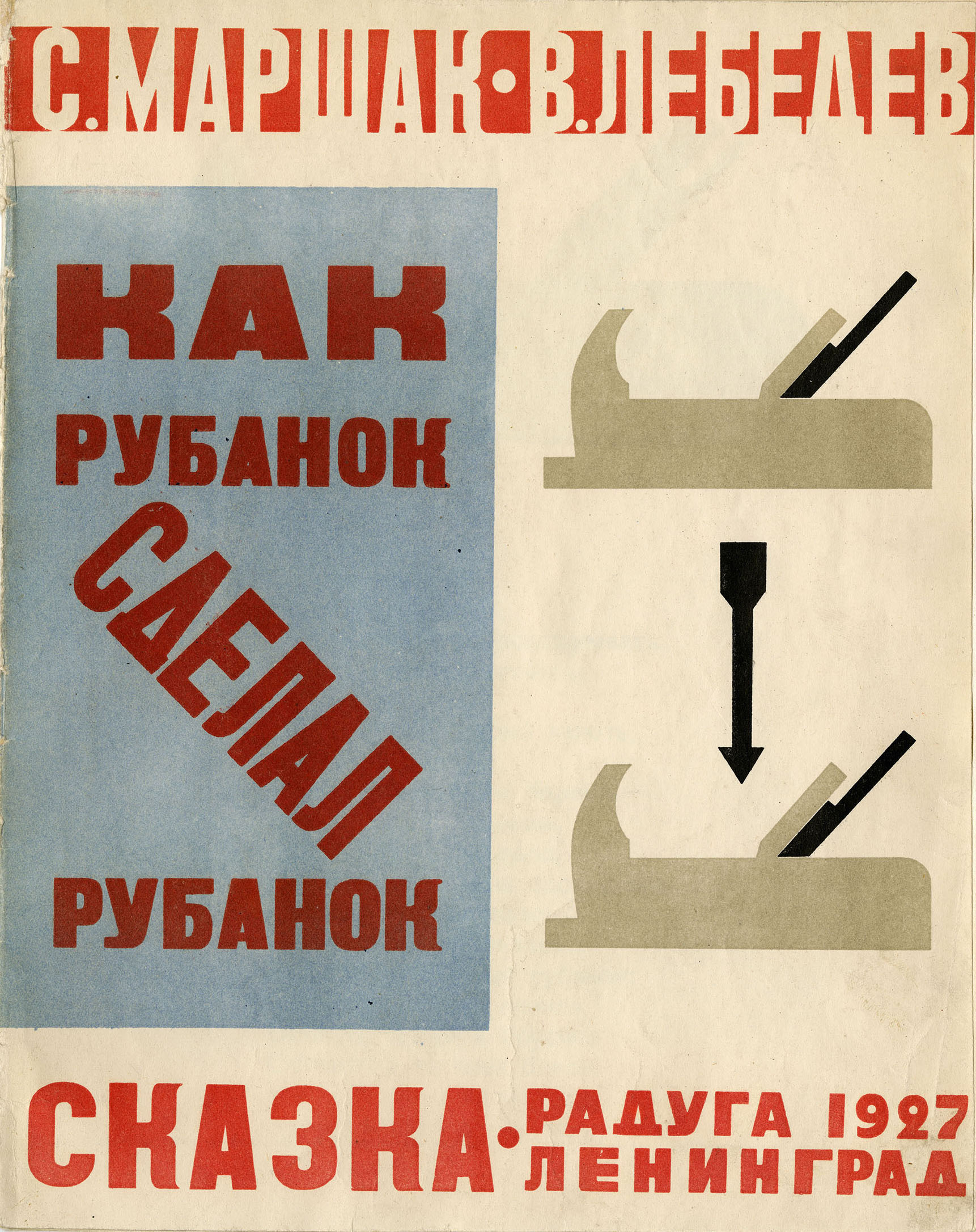

At the same time, in this era the role of the illustrator became particularly important. As Oushakine points out, the creators of new Soviet literature responded to at least two factors: the emergence of a new “mass reader” with diverse comprehension skills, and the ideological concerns of the era, which emphasized useful and realistic literature. Consequently, in content the new literature was expected to be concrete and informative, while in form it placed a strong emphasis on “graphic language,” which foregrounded pictorial elements rather than textual ones, aimed at the illiterate or semiliterate reader. This is one reason why illustrators took on a more significant role: “The book artist increasingly was understood as ‘an author in his or her own right, not just a mere illustrator.’ Covers of many books listed both the writer and the artist as equal contributors” (Oushakine 2016, 172–73, 190; Pokrovskaya 1929, quoted in Oushakine).

The Children’s Book as a Refuge for Avant-Garde Aesthetics

The vaunted experiments of avant-garde art, well known in the West in the form of Constructivist and Suprematist painting and design, and intended for an adult audience, thus also flowered in the Soviet children’s picture book of the 1920s, as we will see in the following essays of this exhibit. “The great artistic-aesthetic experiment of the 1920s . . . found perhaps its fullest, most clearly articulated expression in the art of illustrating and designing children’s books . . . . For a while, until the early 1930s, children’s books would remain a last refuge for . . . Constructivist avant-garde aesthetics” (Steiner 1999, 11 & 175).