“The difference between a wolf and a sheep-dog is not in their size or how they use their tail. An artist should understand that they have many different ways of walking”—Lebedev, 1933 (quoted in Rosenfeld 1999b, 175)

Radical Collaboration

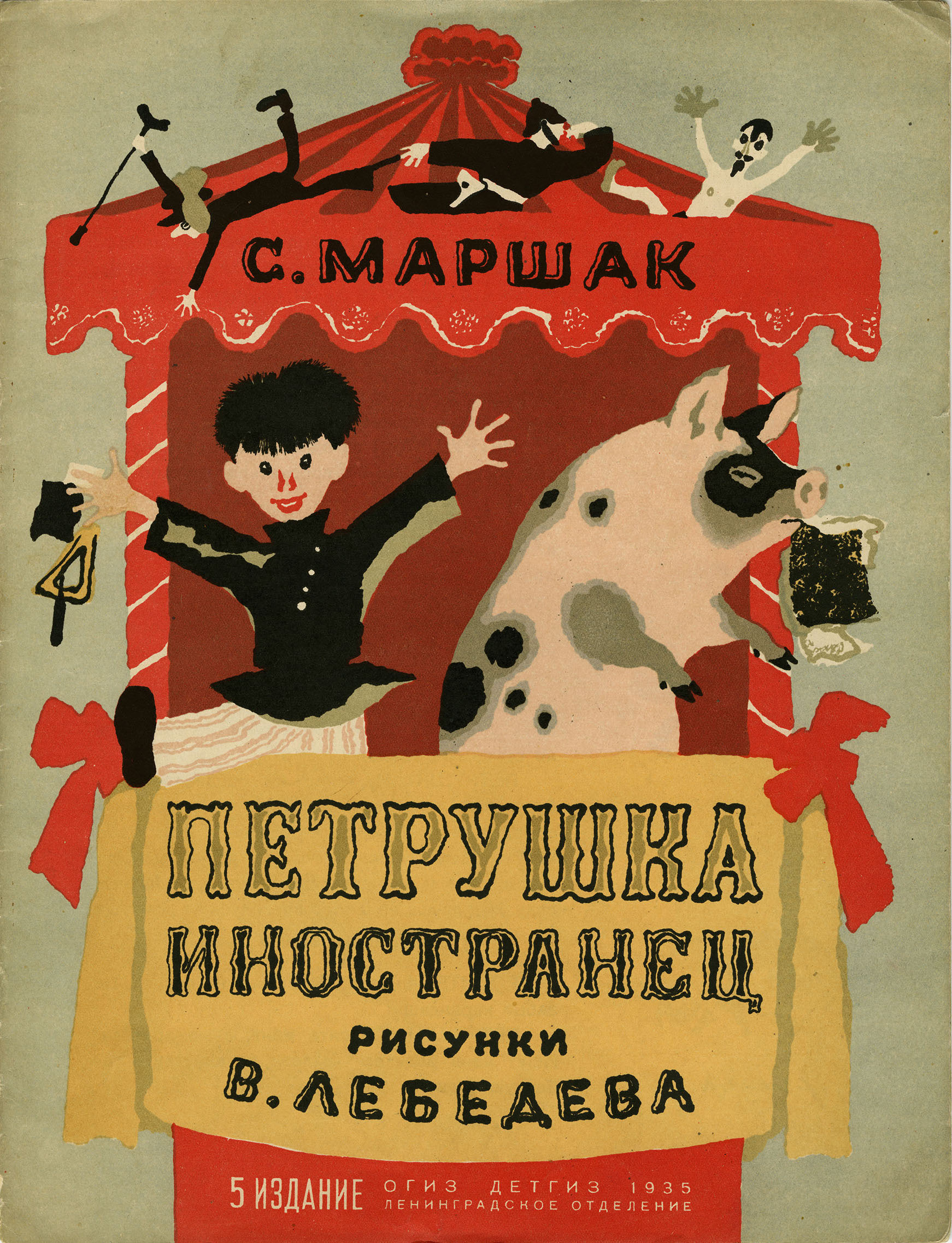

The collaboration between Samuil Marshak (1887–1964) and Vladimir Lebedev (1891–1967) looms large as one of the most innovative collaborations in the history of children’s books. Their works comprise the bulk of the Pamela Harer Collection of Russian Children’s Books, which includes about thirty titles either authored by Marshak or illustrated by Lebedev (approximately fifty books if one includes multiple editions, of which the Harer Collection has a rich array), and over a dozen titles written by them as a team. A portion of these have been digitized for this exhibit, and are available online in the University of Washington Libraries database.

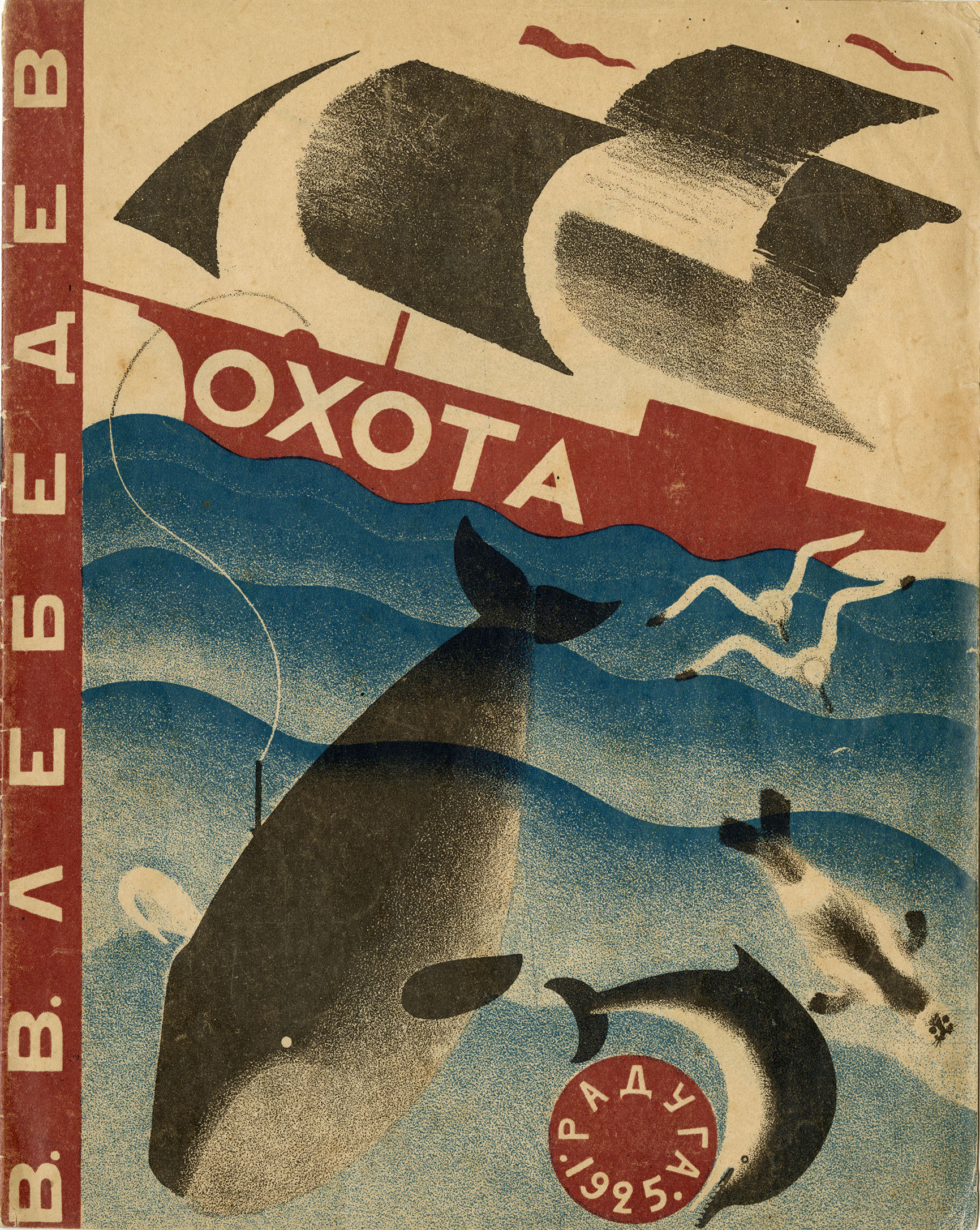

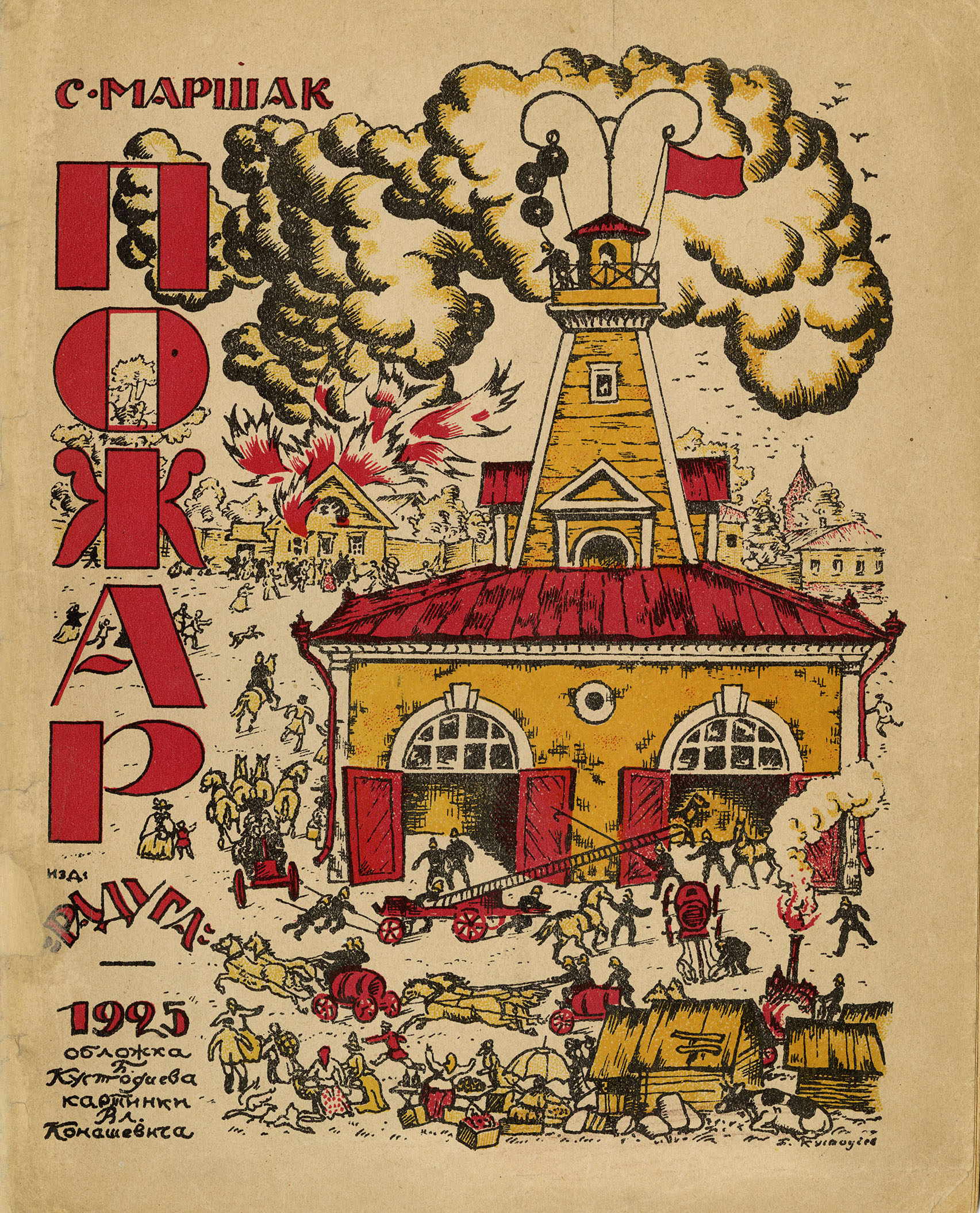

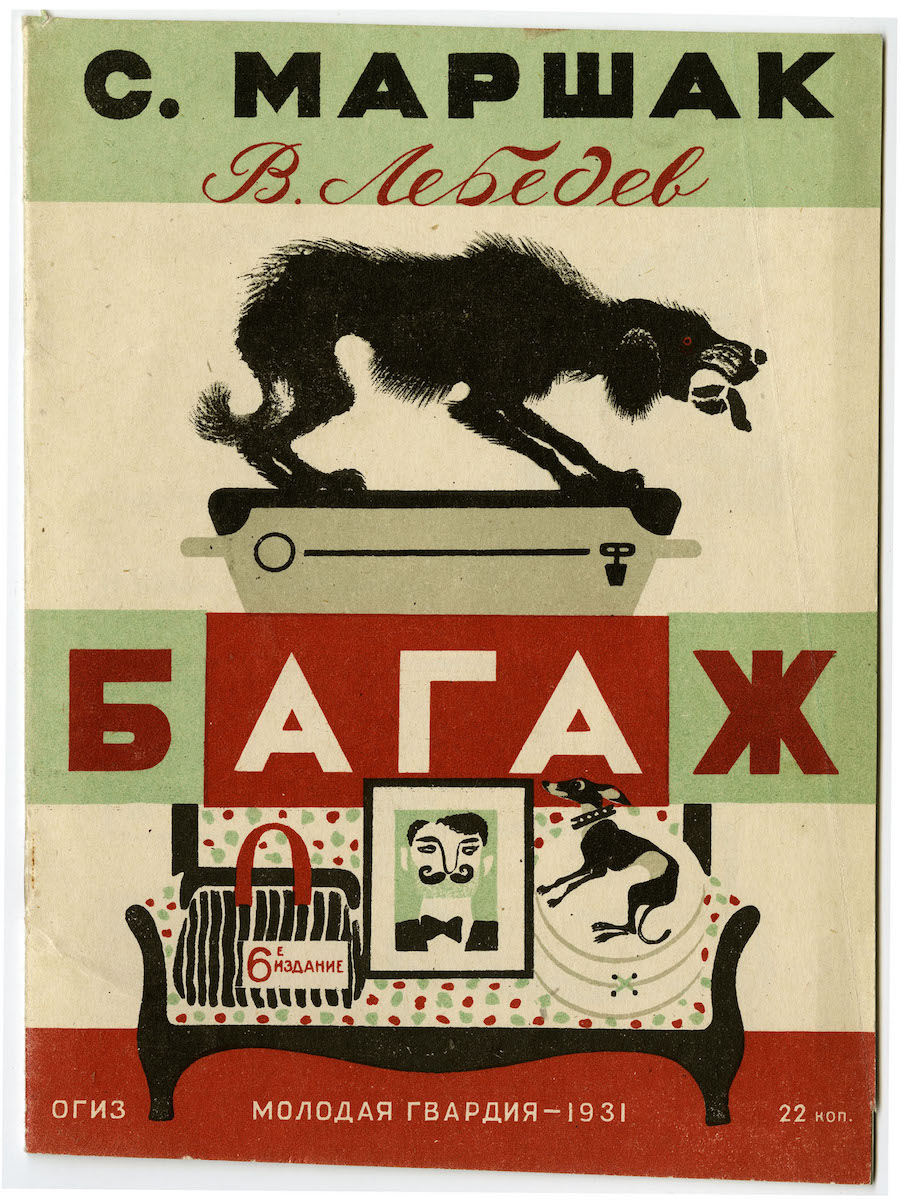

Many of the seminal masterworks created by the Marshak–Lebedev team were published by Raduga (“The Rainbow”), a renowned Soviet publishing house that was founded in 1922 by Lev Kliachko, and then shut down by the government in 1930. In the years 1925–27 alone, together Marshak and Lebedev produced at least seven books for Raduga, including masterworks such as Ice Cream (Мороженое, 1925), The Circus (Цирк, 1925), Yesterday and Today (Вчера и сегодня, 1925), Baggage (Багаж, 1926), and How a Plane Made a Plane (Как рубанок сделал рубанок, 1927). These books embody the beginning of a radically new approach to children’s book design.

Back to Top of Page

Unity of the Book

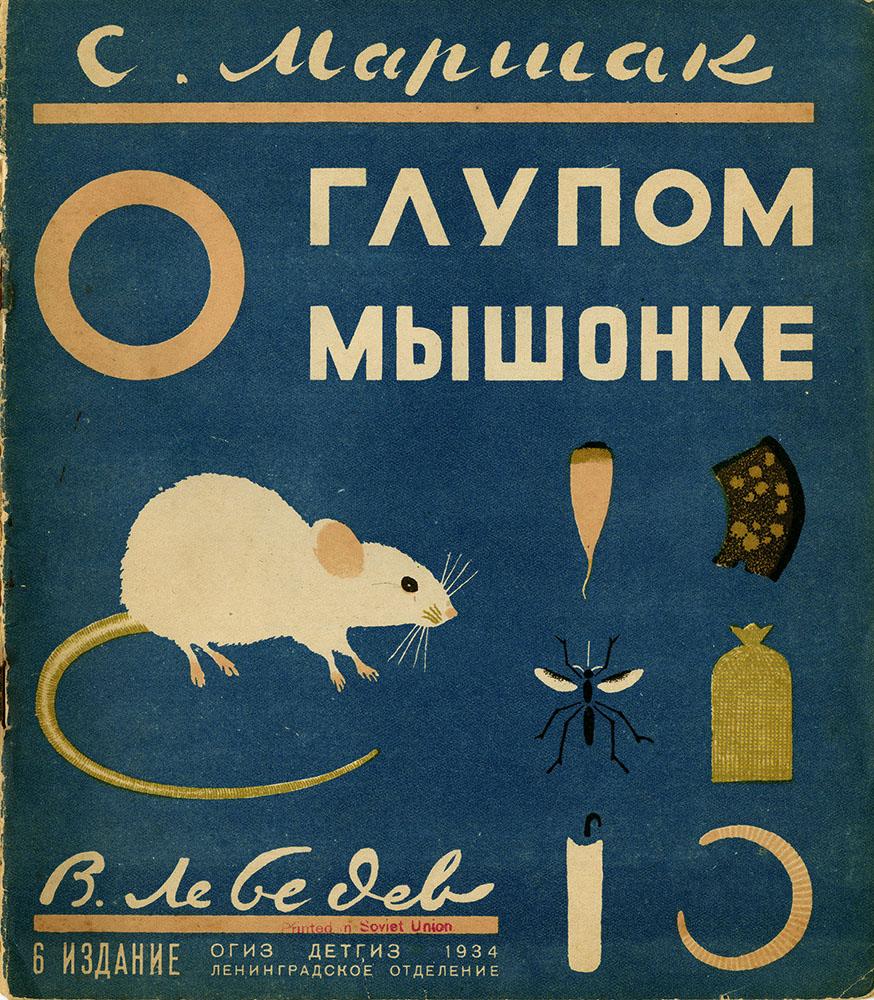

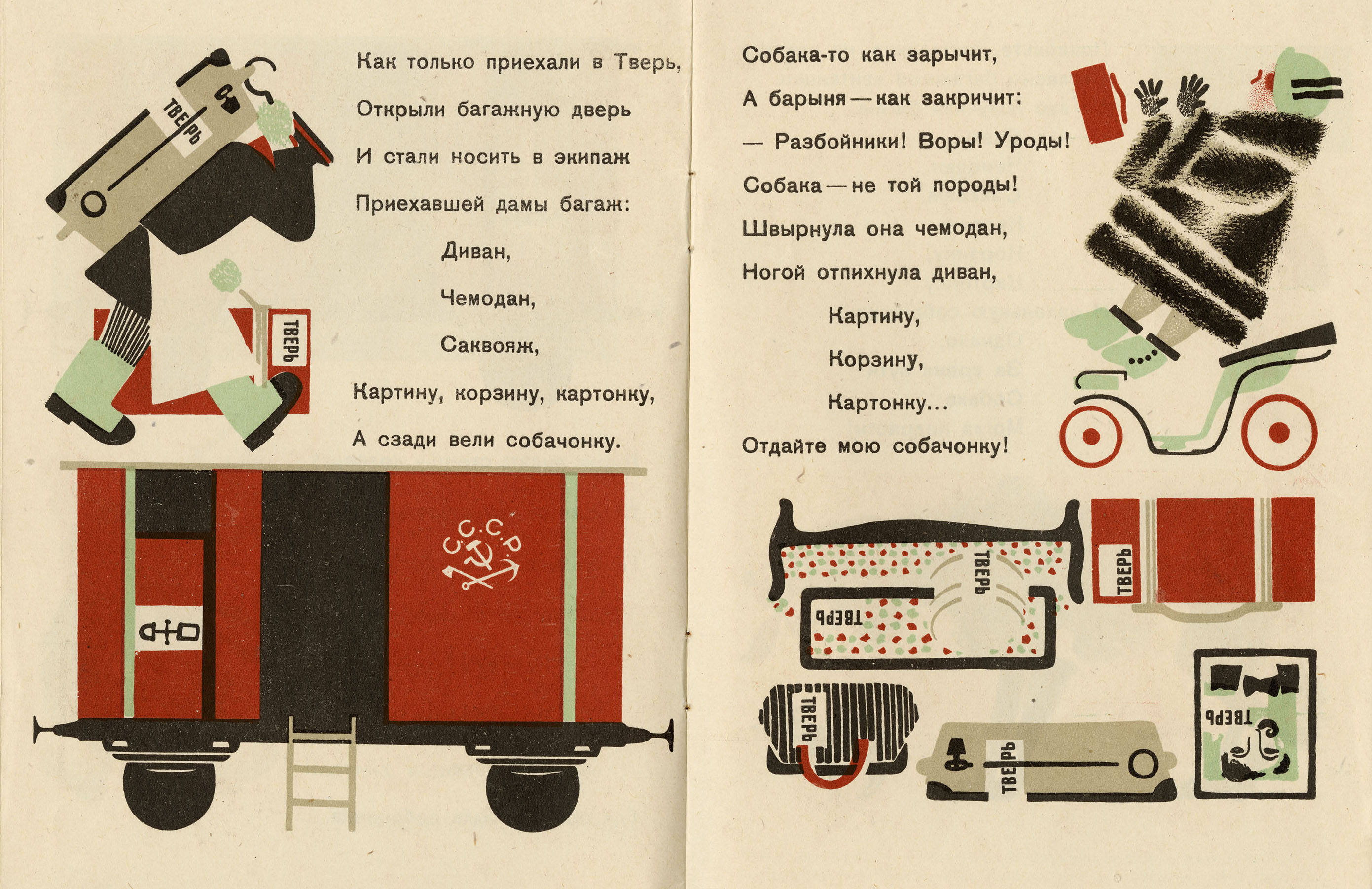

Perhaps ironically, despite the enormous divide between Lebedev’s avant-garde illustrations and the lavish ornamentation of pre-revolutionary books by Alexandre Benois and Ivan Bilibin, a common element is the artist’s emphasis on the book as a complete unity. Lebedev conceived of the children’s book “as an artistic whole” (Kovtun 1996b, 217), and declared: “Every element [of the book] must be subordinated to the unified, overall composition” that supports the artist’s vision (Lebedev 1933). On the front cover of About the Silly Mouse, for instance, the word “about” which is just the letter “O” in Russian, echoes the curved objects of the picture, such as the mouse’s tail and the worm in the lower right-hand corner; these same curves are repeated throughout the book itself. Similarly, in Baggage, Marshak’s short one-word rhyming lines create blocks of text that evoke the rectangular shapes of Lebedev’s designs for the suitcase, purse, and other objects.

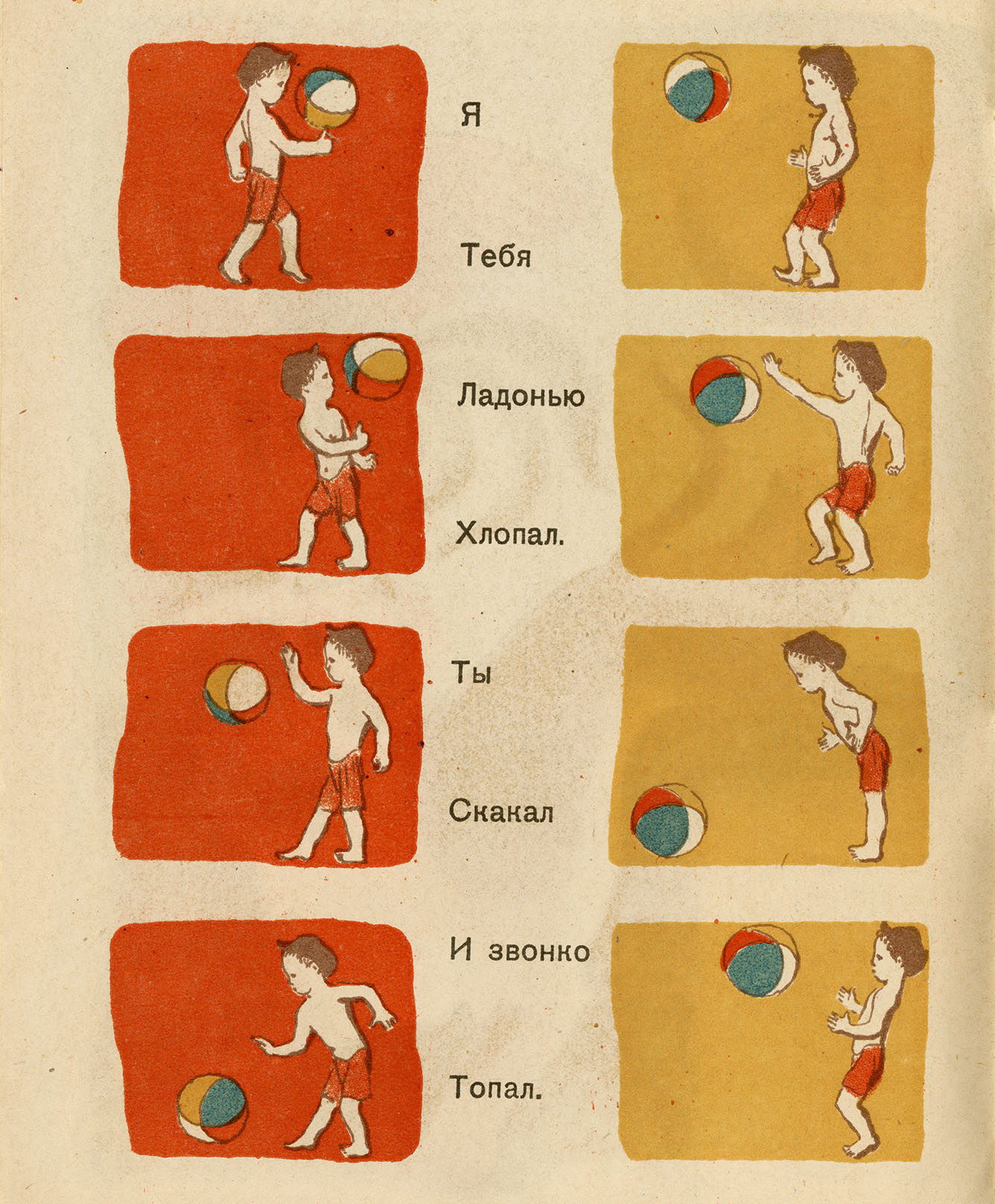

Both Marshak and Lebedev were exceptionally sensitive to the child’s perspective of the world. Marshak later declared that, for a child, “the most humdrum details of everyday life are . . . events of enormous significance.” He also noted the way words and sounds have particular importance to children: “The attitude of children to words . . . is far more serious and trustful than that of grown-ups. They expect any combination of sounds to follow some kind of pattern” (Marshak 1964, 26–28). Lebedev similarly saw a connection to early childhood perception as essential to his art: “An artist working on a children’s book must be able to access that feeling of excitement that he experienced in childhood. When I work on a book for children, I try to recall the perception of the world that I had as a child” (Lebedev 1933).

Back to Top of Page

Biographical Background: Samuil Marshak

Samuil Marshak has been called “the Russian Lewis Carroll” (Marshak 1964, 12). He was born in Voronezh, spent much of his childhood in and near Ostrogozhsk, and moved to St. Petersburg as a teenager. In the 1910s, Marshak spent two years as a foreign correspondent in England, where he discovered British poets such as Wordsworth and Browning, as well as the works of Lewis Carroll and the rich tradition of English nursery rhymes, which proved to be very significant to his development as a writer. While in England, Marshak began translating English poetry and writing poetry for children. He later described his discovery of English children’s literature while attending classes at the University of London: “Above all, it was the university library that taught me to love English poetry. In those crowded . . . rooms, whose windows looked out over . . . the barges of the Thames, I first . . . stumbled upon English children’s folklore, marvelous and full of whimsical humor” (Marshak 1968–72, 1:9).

Back to Top of Page

Sounds and rhythms were an essential ingredient of Marshak’s relation to language. As he later recounted in his autobiography: “I was ‘writing poetry’ before I learned to write. I used to make up couplets, and even quatrains, orally, to myself . . . . Gradually this ‘oral tradition’ was replaced by written verse” (1964, 135–36). In the 1920s, Marshak became a dominant figure in children’s literature in Leningrad. He published his first poems for children in 1923, and started collaborating with a new magazine for children, The Sparrow (Воробей, 1923–24), later renamed The New Robinson (Новый Робинсон, 1924–25) (Hellman 2013, 318–20; Marshak 1964; Sokol 1984, 94–98. For a discussion of Marshak’s “mythologization” of his own childhood in his autobiography, see Balina 2008a).

Back to Top of Page

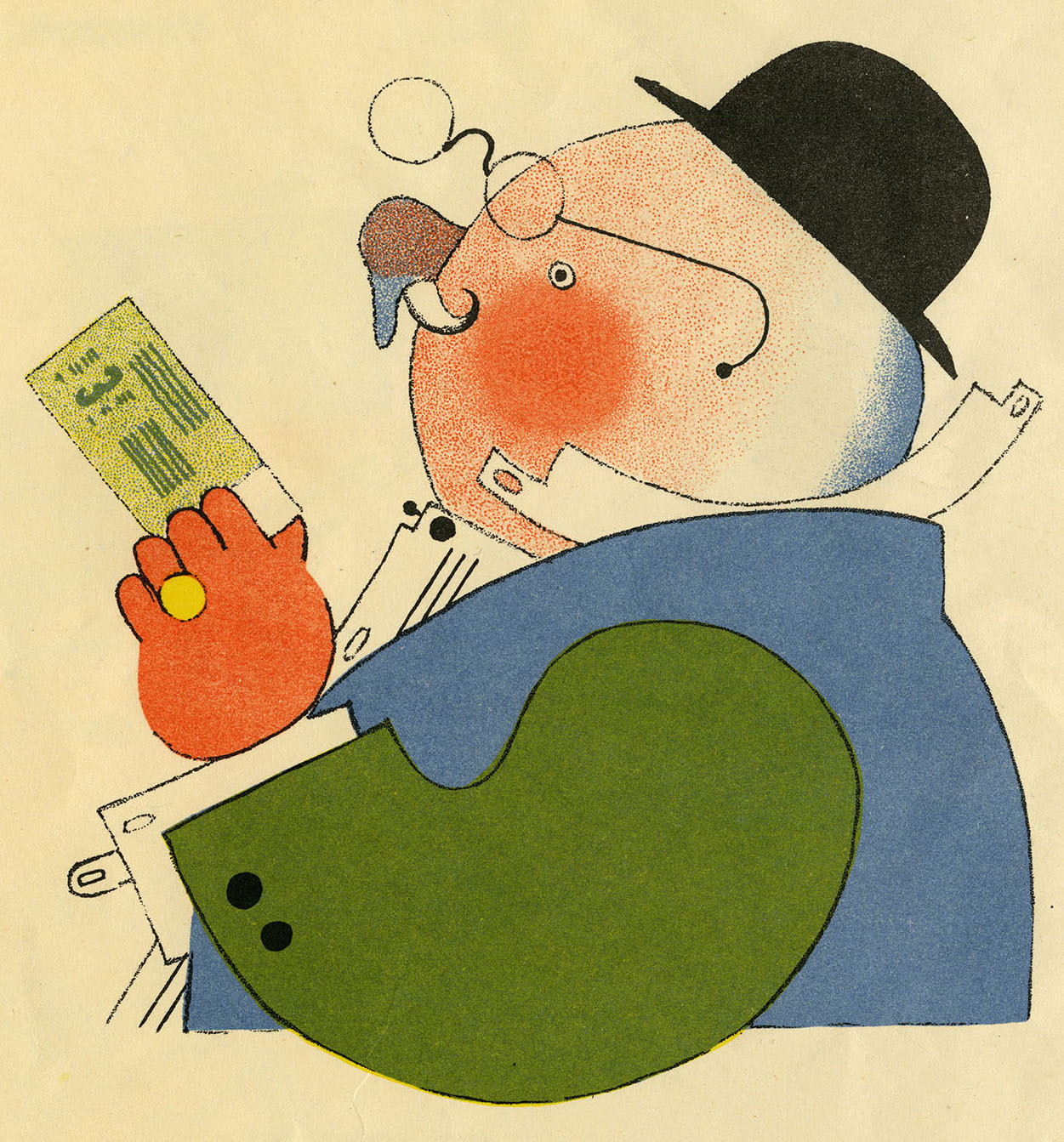

Vladimir Lebedev is widely regarded as the preeminent Soviet designer of children’s books in the 1920s. He has been called the “king of the children’s book” (Andrei Chegodaev, quoted in Lemmens & Stommels 2009, 98; Rothenstein & Budashevskaya 2013, 27). Born and raised in St. Petersburg (which became Leningrad in the Soviet era), Lebedev began drawing as a child, and published his first artworks in journals as a teenager. His roots were in satirical illustration: he published numerous caricatures in satirical magazines both before and after the revolution. In 1912, Lebedev began studying at both the St. Petersburg Academy of Fine Arts and the private studio of Mikhail Bernshtein, where he became acquainted with avant-garde artists of the era such as Vladimir Tatlin (Petrov 1971; Rosenfeld 2003, 199–216; White 1988, 84–88). An important element of Lebedev’s early career was his avant-garde poster-design for the Russian Telegraph Agency (ROSTA; for details, read this essay), which foreshadowed the techniques he used in his children’s book illustrations just a few years later.

Back to Top of Page

The Primitive Scarecrow

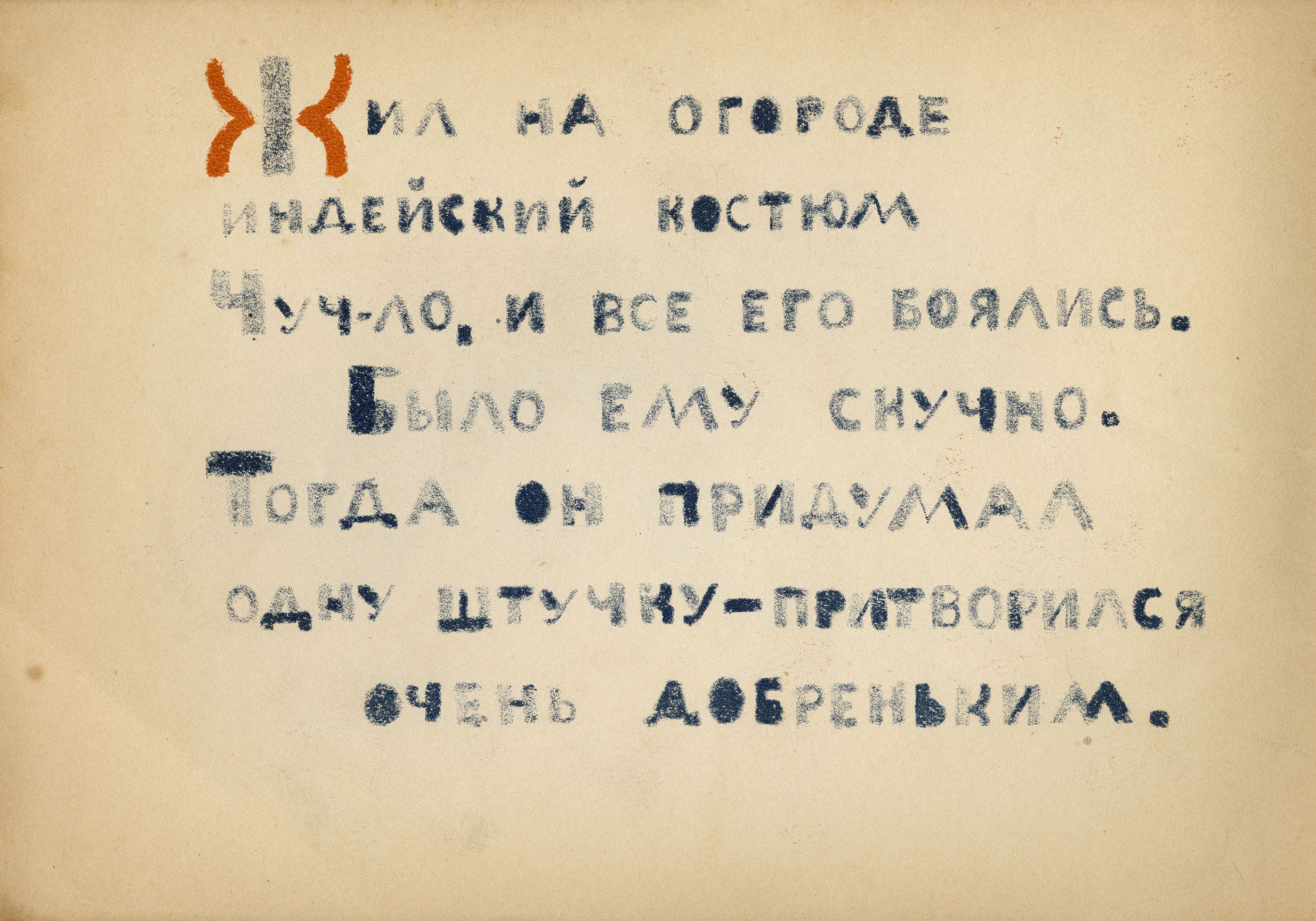

Following his work for the ROSTA Windows, Lebedev made a great splash in the world of children’s book design in 1922, with two children’s books, The Elephant’s Child (Слонёнок) and The Adventures of Scarecrow (Приключения Чуч-ло), which were widely admired for their innovative application of avant-garde methods to children’s illustration. In Lebedev’s “pathbreaking” Elephant’s Child, he deconstructed the animal figures into “simplified geometric components and monochromatic fields of color” (Weld 2018, 53). Steiner notes that these “Cubist constructions . . . made an enormous aesthetic impression on Lebedev’s contemporaries as well as generations of critics to come” (1999, 43).

Lebedev’s artwork and handwritten lettering in The Adventures of Scarecrow, on the other hand, evoke the Neo-Primitivist, Cubo-Futurist books of 1912–13 by Aleksei Kruchenykh, Mikhail Larionov, Natalya Goncharova, and others, who used lithography to evoke a handcrafted quality and sometimes imitated children’s stencils or rubber-stamps (Gourianova 1999; Compton 1978, esp. 72–73), as discussed in more detail in this essay on the lubok (illustrated broadside). Weld notes that Scarecrow is constructed to resemble the pretend-play of a child, with awkward block-lettering and a deliberately naïve child’s point of view. These early works underscore Lebedev’s fascination with the child’s perspective of the world and the avant-garde “infantile aesthetic” (Weld 2018, 62–66).

Back to Top of Page

Collaboration at the State Publishing House (Gosizdat)

Together Marshak and Lebedev not only created a new style and visual vocabulary for the picture book in the 1920s, but also served as beloved mentors to an entire generation of artists and writers, who are often collectively referred to as the “Leningrad School of Children’s Books” or “the Lebedev School” (Lemmens & Stommels 2009, 113–15; Rosenfeld 1999b, 170). In 1924, Marshak and Lebedev took charge of the Leningrad division of the new Children’s Literature Department (Detotdel) of the State Publishing House (Gosizdat, or GIZ), which was located atop the famous Singer Building on Nevsky Prospect. Marshak was the literary editor, Lebedev was the artistic director, and together they worked with and nurtured an outstanding cadre of writers and artists, such as Vitaly Bianki, Boris Zhitkov, Evgeny Charushin, Vladimir Konashevich, Vera Yermolaeva, and Mikhail Tsekhanovsky. Many sources refer to this seminal publishing house of the 1920s as “Detgiz,” although Detgiz per se was not officially established as a publishing house until the 1930s. Regardless, the term “Detgiz” has often served as an informal designation for the 1920s operation.

Birth of the Book

Marshak was known as a legendary editor, remembered later with great fondness by those he mentored: “Marshak united us; he was the center around which everything turned . . . . His editorial work was not a craft but an art . . . . In that process there occurred the miraculous birth not only of the book, but of the author himself” (Isai Rakhtanov 1971, quoted in Sokol 1984, 98). Lebedev was also remembered as an outstanding and exacting mentor to other artists. He corrected their drawings “with great passion and persistence,” and insisted that they learn the technical side of book production: “He required that the artist himself transfer his drawing to a lithographic stone rather than leaving this task to the printer.” Yet Lebedev did not impose his own artistic views, instead “encouraging each artist to bring his or her own individual style and creative originality into children’s books” (Vlasov, Schwartz, and Kovtun, quoted in Rosenfeld 2003, 212–13; 246–47).

Back to Top of Page