“Look how avid children are for illustrated books. They are prepared to read the driest and most boring text, if it explains to them the content of a picture” –Vissarion Belinsky (in Hellman 2013, 74).

"How society wished itself to be"

Because childhood itself is notoriously difficult to define, its boundaries and characteristics shifting over the centuries, an unambiguous definition of children’s literature also eludes our grasp. “Nobody is quite sure what children’s literature is, and therefore constructing its history is a contentious business,” Peter Hunt usefully points out, noting that children’s literature often reflects an idealized version of how adults wish to view themselves: “These books give us a remarkable picture of how society wished itself to be . . . and thus, often inadvertently, give us a picture of how it actually was” (1995, ix & xi).

Back to Top of Page

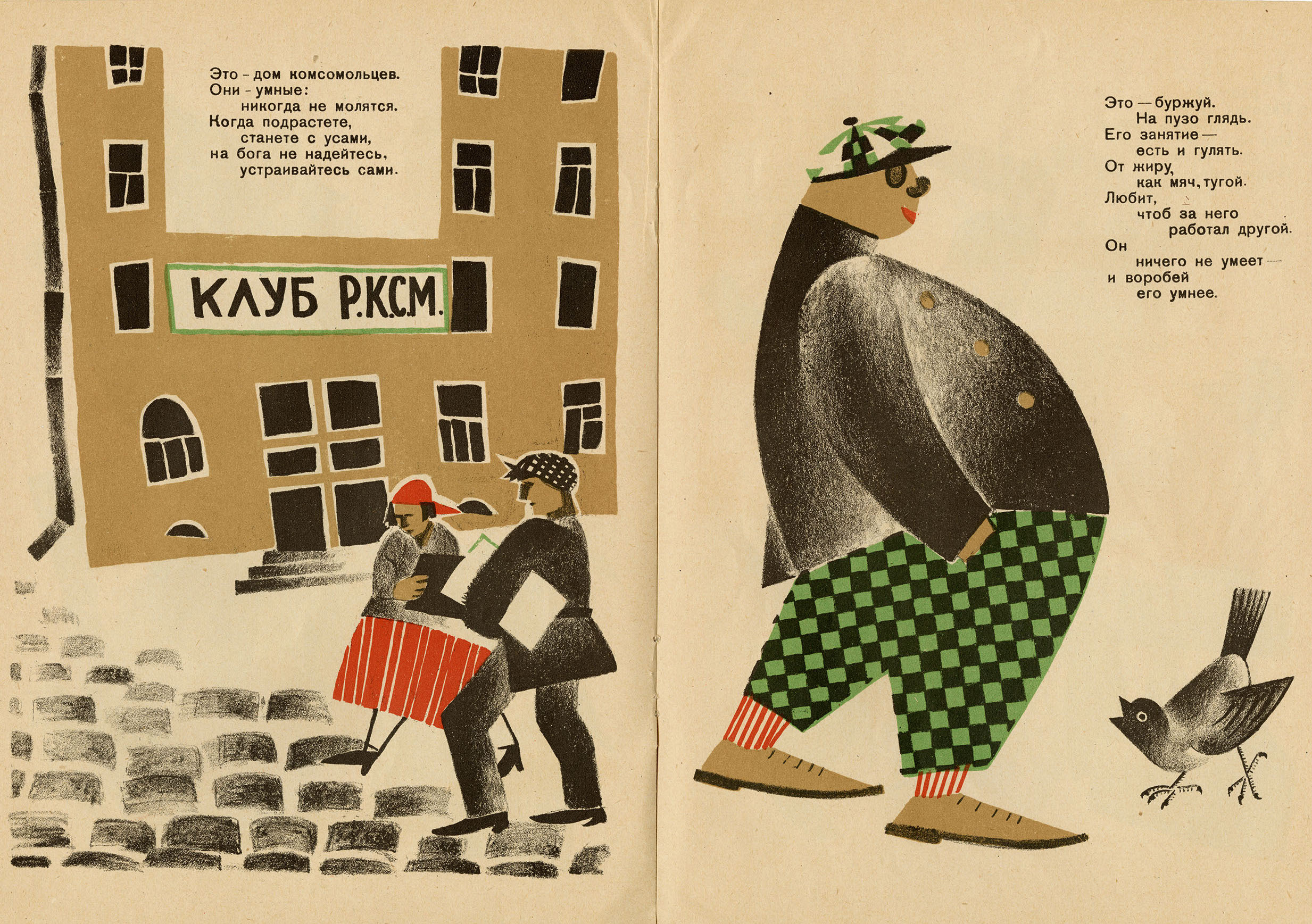

The Komsomol vs. the Fat Bourgeois

Meanwhile, children’s literature has frequently swung between two poles: viewed as a vehicle for either entertainment or didacticism, it engenders passionate arguments regarding the role of the word and image in a child’s life. Although often depicted as a clear progression from didacticism to entertainment, the history of children’s literature, in fact, has swerved unevenly between these realms, and this is particularly true when one broadens one’s perspective to include the context of Russia and Eastern Europe.

Back to Top of Page

Letters & Trains

There is a further tension between the role of words and images in the children’s book. As picture-book theorists have argued, the relationship between text and image can be ironic or disjunctive, symmetrical or contrapuntal, and this interplay is often the source of the pleasure in reading a picture book (see Nikolajeva & Scott 2001, 1–12; Weld 2018, 21–23). The reader—usually a child—repeatedly returns to the details of the words and illustrations, each time discovering new meaning in their intertwined relation.

Back to Top of Page

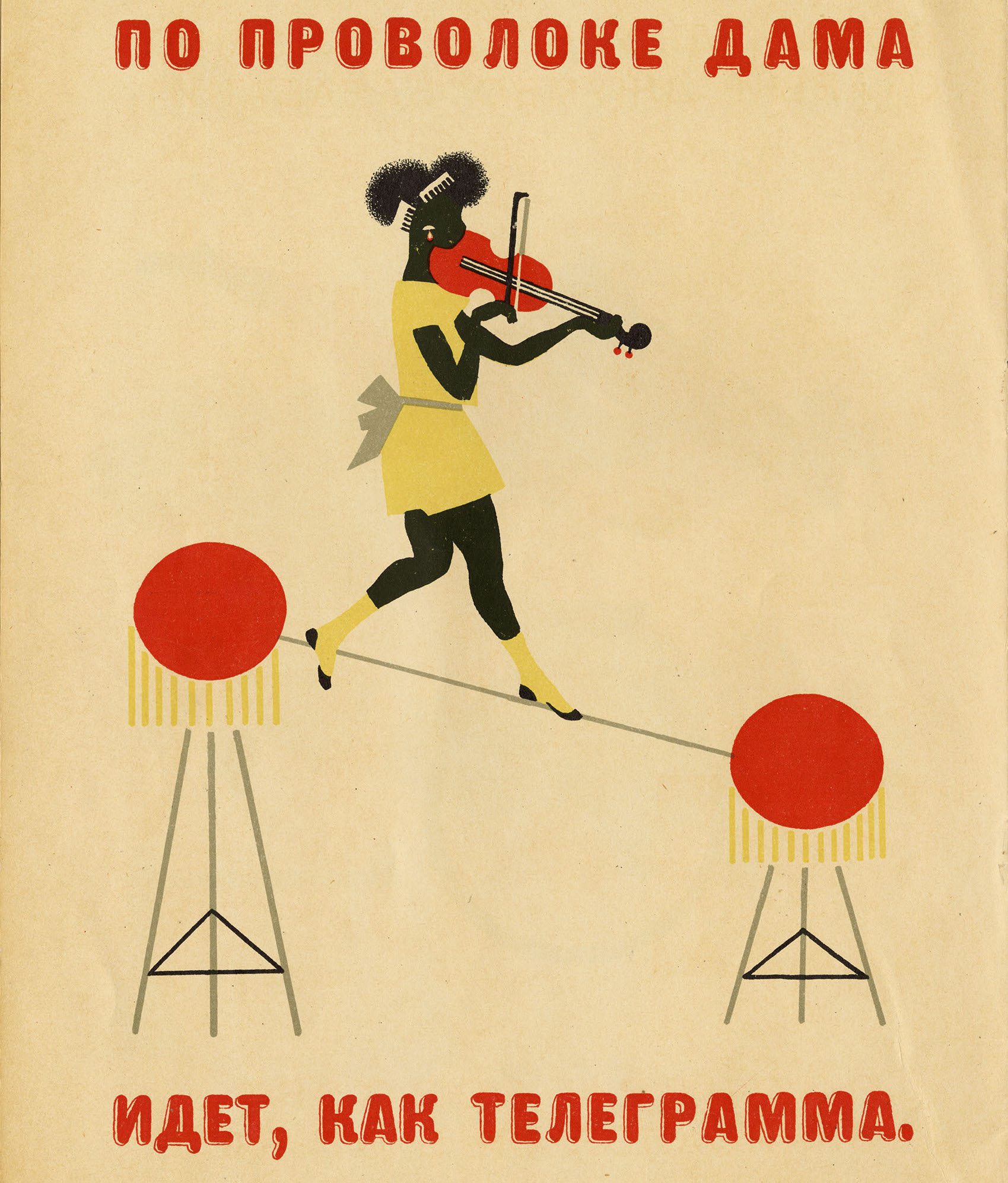

Lady on a Wire

“If we look carefully, in fact, the words in picture books always tell us that things are not merely as they appear in the pictures, and the pictures always show us that events are not exactly as the words describe them. Picture books are inherently ironic, therefore: a key pleasure they offer is a perception of the differences in the information offered by pictures and texts” (Nodelman 2005, 137). Weld argues that the picture book “uniquely combines image and text into a complex signifying whole, . . . where the interplay of word and image . . . are on truly equal footing . . . . [It] ‘functions as a sequential visual narrative, a literary work, a mediating object, and a tangible material artifact’” (Weld 2018, 21–23; with quote by op de Beeck).

Back to Top of Page

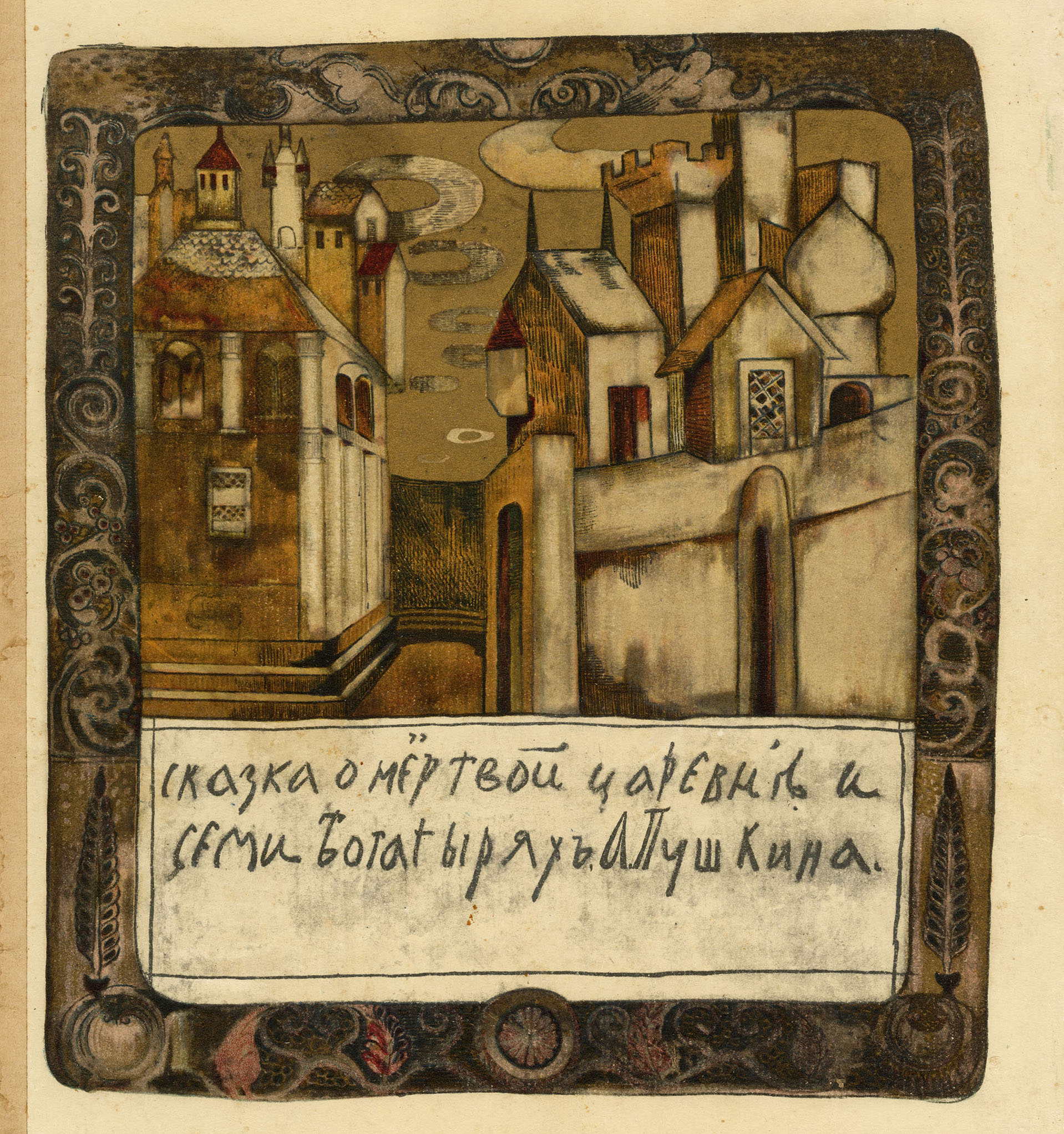

The Hand-Crafted Fairytale

One could argue that not only the illustrations, but also the physicality of the book itself—the weight of its pages, however tattered, and the texture of its cover, however stained or warped—often hold the highest place in a child’s memory. Lerer notes that the history of children’s literature is “a history, too, of artifacts: of books as valued things, crafted and held” (2008, 322).

Back to Top of Page

Electric Dance of Word & Image

In its tangible materiality, the picture book entices the reader/viewer with its bipartite dance of word and image, which conveys information that is both different and the same, both complementary and contradictory, thus creating “a whole from the component parts—but without those parts ever actually blended into one” (Nodelman 1988, 21). In this exhibit we will pay particular attention to that dual history of word and image, and the ways in which they mirror and contradict each other when they join forces in the robust medium of the picture book.

Back to Top of Page